-

Welcome to the Community Forums at HiveWire 3D! Please note that the user name you choose for our forum will be displayed to the public. Our store was closed as January 4, 2021. You can find HiveWire 3D and Lisa's Botanicals products, as well as many of our Contributing Artists, at Renderosity. This thread lists where many are now selling their products. Renderosity is generously putting products which were purchased at HiveWire 3D and are now sold at their store into customer accounts by gifting them. This is not an overnight process so please be patient, if you have already emailed them about this. If you have NOT emailed them, please see the 2nd post in this thread for instructions on what you need to do

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

RELEASED Hivewire Big Cat Has Begun!

- Thread starter Chris

- Start date

I also hope, at some point, we'll see a Snow Leopard. ~hint, hint, hint~

I;d like to as well... Gonna be a big challenge painting all those beautiful spots, I can say that

Oh I can well imagine it would be. I was dropping a hint . . . just in case you already had started one.

Not yet

Sorry for your loss.He is very much in the works/almost finished/heading out for beta testing this week- got sidetracked last week with the death of my friend Carol... You WILL of course need the tiger though to use my White Tiger texture set

Yes, I know would need the base, just wanted to get them all at once but somehow he came home with me anyway

Congrats on the Tiger release. I've been playing with it today (in-between working on birds). It's a really nice model, the materials are simple amazing and renders well right out of the box.

To inspire all you starting on renders, here's a BBC article/video released today about Tigers. I'll have to create some attack/defense poses for my crane now that I have a great looking tiger to play with.

To inspire all you starting on renders, here's a BBC article/video released today about Tigers. I'll have to create some attack/defense poses for my crane now that I have a great looking tiger to play with.

Doc Acme

Motivated

Thank you, thank you! Bengal's are one of my favorite "kittys".

Spent the day converting to a Lightwave format, in that I'm able to weight map the fur so it's animated as well.

Still need to do some minor tweeks, but he's 99+% there.

I got lucky in that even though I had to do some significant changes to the skeletal rig, mostly scaling, I'm still able to export & use the Poses from Daz. Some areas such as the paws & tail still need tweeking after importing the pose, but I've some great 3rd party tools so that's only taking seconds now.

So, when might we expect the cub?

Spent the day converting to a Lightwave format, in that I'm able to weight map the fur so it's animated as well.

Still need to do some minor tweeks, but he's 99+% there.

I got lucky in that even though I had to do some significant changes to the skeletal rig, mostly scaling, I'm still able to export & use the Poses from Daz. Some areas such as the paws & tail still need tweeking after importing the pose, but I've some great 3rd party tools so that's only taking seconds now.

So, when might we expect the cub?

Saving the Tiger

Of all the big cats, Tigers are the most persecuted and closest to extinction. Over the last century tiger numbers have dwindled from almost 100,000 to less than 3,200. The tiger was formerly classified into nine subspecies, three of which (the Javan, Bali and Caspian) are extinct and one, the South-China subspecies, has not been sighted in the last decade, and may presumably be extinct. With nine subspecies it is difficult, if not impossible, to reintroduce a subspecies into an area where it is going extinct like introducing the Bengal tiger to improve the genetic pool of the South-China tiger. It will no longer be "purebred". The tiger is the least diverse of all the big cats. It is believed that the low genetic diversity in tigers was caused by a population decline during the ice age 110,000 years ago. Recently, modern phylogenetic DNA studies have suggested that there are only two subspecies (the Continental and the Sunda subspecies) of the tiger and not nine as previously thought. If this is accepted as true, it will be easier to conserve the tiger in the future. However, another recent study (2018) has thrown a spanner into the works. Researchers from China and the US looked at the whole genomes of 32 representative tigers and found that there were indeed nine subspecies of tiger. There is a downside to considering tigers as separate subspecies and attempting to protect them on this basis, without mixing in tigers from elsewhere. Genetic diversity is key for adaptation and ultimately species survival. As our understanding increases, more informed decisions can be made regarding how best to conserve the tiger.

At the Tiger Summit held in St Petersburg, Russia in November 2010, the 13 tiger range countries adopted a Global Tiger Recovery Program. The goal is to effectively double the number of wild Tigers by 2022 through actions to:

effectively preserve, manage, enhance and protect tiger habitats;

eradicate poaching, smuggling and illegal trade of tigers, their parts and derivatives;

cooperate in transboundary landscape management and in combating illegal trade;

engage with indigenous and local communities;

increase the effectiveness of Tiger and habitat management; and

restore Tigers to their former range.

Saving tigers is about more than restoring a single species. As a large predator, tigers play an important role in maintaining a healthy ecosystem. Every time we protect a tiger, we protect around 25,000 acres of forest - forests that sustain wildlife and local communities and supply people around the world with clean air, water, food, and products. There seemed to be some progress. Based on the best available information, tiger populations are stable or increasing in India, Nepal, Bhutan, Russia and China. An estimated 3,900 tigers remain in the wild, but much more work is needed to protect this species if we are to secure its future in the wild. In some areas, including much of Southeast Asia, tigers are still in crisis and declining in number.

Since 2017, IUCN has recognized two tiger subspecies, commonly referred to as the Continental tiger and the Sunda Island tiger. All remaining island tigers are found only in Sumatra, with tigers in Java and Bali now extinct. These are popularly known as Sumatran tigers. The continental tigers currently include the Bengal, Malayan, Indochinese and Amur (Siberian) tiger populations, while the Caspian tiger is extinct in the wild. The South China tiger is believed to be functionally extinct.

The Tiger's closest living relative is the Snow Leopard. They diverge earlier than the lion, leopard and the jaguar (which are closely related). The Snow Leopard is unique among the Panthera. It is the only one that is unable to roar. Indeed, until recently it was considered different enough to be placed in a separate genus of its own, Uncia. It was only with genetic testing that established the fact that its nearest relative is the tiger and that it belonged in the Panthera genus.

Of all the big cats, Tigers are the most persecuted and closest to extinction. Over the last century tiger numbers have dwindled from almost 100,000 to less than 3,200. The tiger was formerly classified into nine subspecies, three of which (the Javan, Bali and Caspian) are extinct and one, the South-China subspecies, has not been sighted in the last decade, and may presumably be extinct. With nine subspecies it is difficult, if not impossible, to reintroduce a subspecies into an area where it is going extinct like introducing the Bengal tiger to improve the genetic pool of the South-China tiger. It will no longer be "purebred". The tiger is the least diverse of all the big cats. It is believed that the low genetic diversity in tigers was caused by a population decline during the ice age 110,000 years ago. Recently, modern phylogenetic DNA studies have suggested that there are only two subspecies (the Continental and the Sunda subspecies) of the tiger and not nine as previously thought. If this is accepted as true, it will be easier to conserve the tiger in the future. However, another recent study (2018) has thrown a spanner into the works. Researchers from China and the US looked at the whole genomes of 32 representative tigers and found that there were indeed nine subspecies of tiger. There is a downside to considering tigers as separate subspecies and attempting to protect them on this basis, without mixing in tigers from elsewhere. Genetic diversity is key for adaptation and ultimately species survival. As our understanding increases, more informed decisions can be made regarding how best to conserve the tiger.

At the Tiger Summit held in St Petersburg, Russia in November 2010, the 13 tiger range countries adopted a Global Tiger Recovery Program. The goal is to effectively double the number of wild Tigers by 2022 through actions to:

effectively preserve, manage, enhance and protect tiger habitats;

eradicate poaching, smuggling and illegal trade of tigers, their parts and derivatives;

cooperate in transboundary landscape management and in combating illegal trade;

engage with indigenous and local communities;

increase the effectiveness of Tiger and habitat management; and

restore Tigers to their former range.

Saving tigers is about more than restoring a single species. As a large predator, tigers play an important role in maintaining a healthy ecosystem. Every time we protect a tiger, we protect around 25,000 acres of forest - forests that sustain wildlife and local communities and supply people around the world with clean air, water, food, and products. There seemed to be some progress. Based on the best available information, tiger populations are stable or increasing in India, Nepal, Bhutan, Russia and China. An estimated 3,900 tigers remain in the wild, but much more work is needed to protect this species if we are to secure its future in the wild. In some areas, including much of Southeast Asia, tigers are still in crisis and declining in number.

Since 2017, IUCN has recognized two tiger subspecies, commonly referred to as the Continental tiger and the Sunda Island tiger. All remaining island tigers are found only in Sumatra, with tigers in Java and Bali now extinct. These are popularly known as Sumatran tigers. The continental tigers currently include the Bengal, Malayan, Indochinese and Amur (Siberian) tiger populations, while the Caspian tiger is extinct in the wild. The South China tiger is believed to be functionally extinct.

The Tiger's closest living relative is the Snow Leopard. They diverge earlier than the lion, leopard and the jaguar (which are closely related). The Snow Leopard is unique among the Panthera. It is the only one that is unable to roar. Indeed, until recently it was considered different enough to be placed in a separate genus of its own, Uncia. It was only with genetic testing that established the fact that its nearest relative is the tiger and that it belonged in the Panthera genus.

Question: When is a Sabertooth cat NOT a cat?

Answer: When it belongs to the related families of Barbourofelidae and Nimravidae and not Felidae.

Barbourofelis fricki, a barbourofelid, and Eusmilus sicarius, a nimravid are two sabertooths with the most extreme sabertooth adaptation ever seen, even more so than Smilodon! Their canines are relatively longer than those of Smilodon so much so they have flanges on their mandibles to protect them. Their hind limbs are almost plantigrade so as to stabilise them when they pull down larger prey. They were both originally thought to be true cats and were at one time classified as cats in the family Felidae, the so called "Paleofelids". Later it was found that they had a different bone structure in the small bones of the ear. They were then placed in a new family, the Nimravidae. In the early 2000's, however, further studies indicate that the barbourfelids were actually closer related to the true cats than they were to the nimravids and so they (the barbourofilids) were placed in a family of their own, the Barbourofelidae.

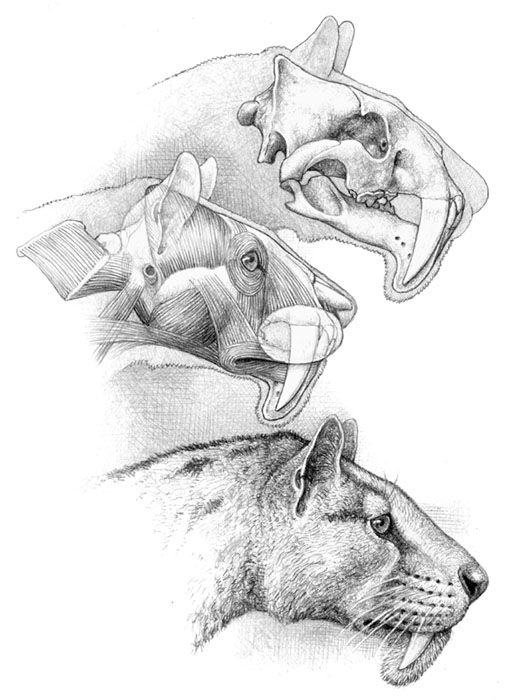

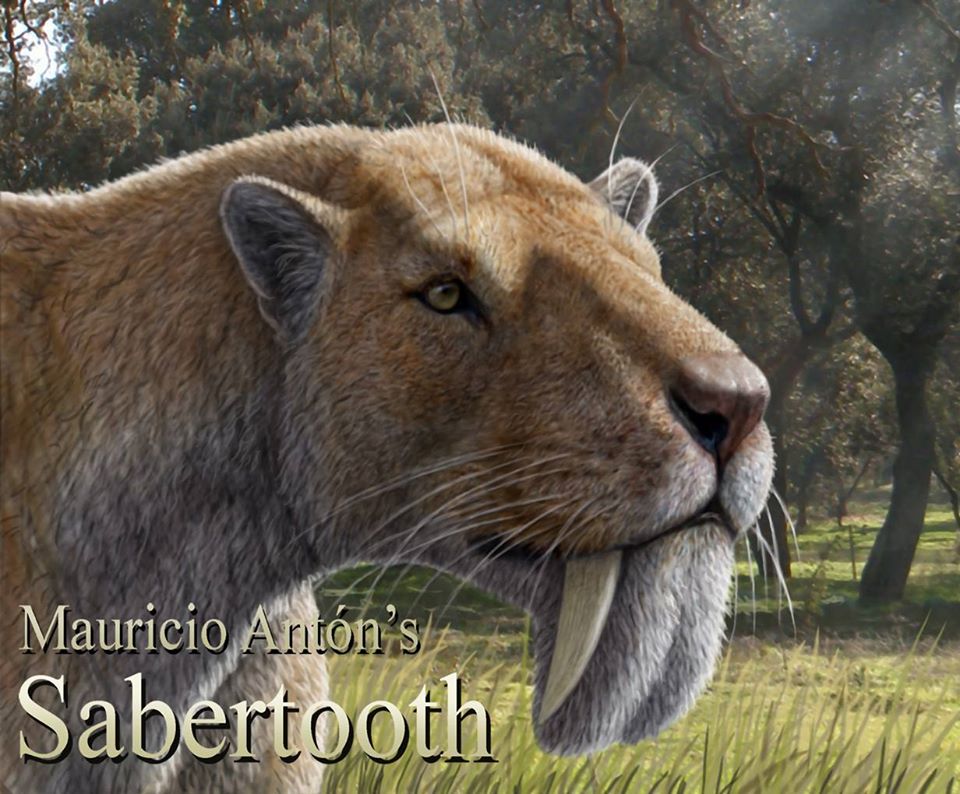

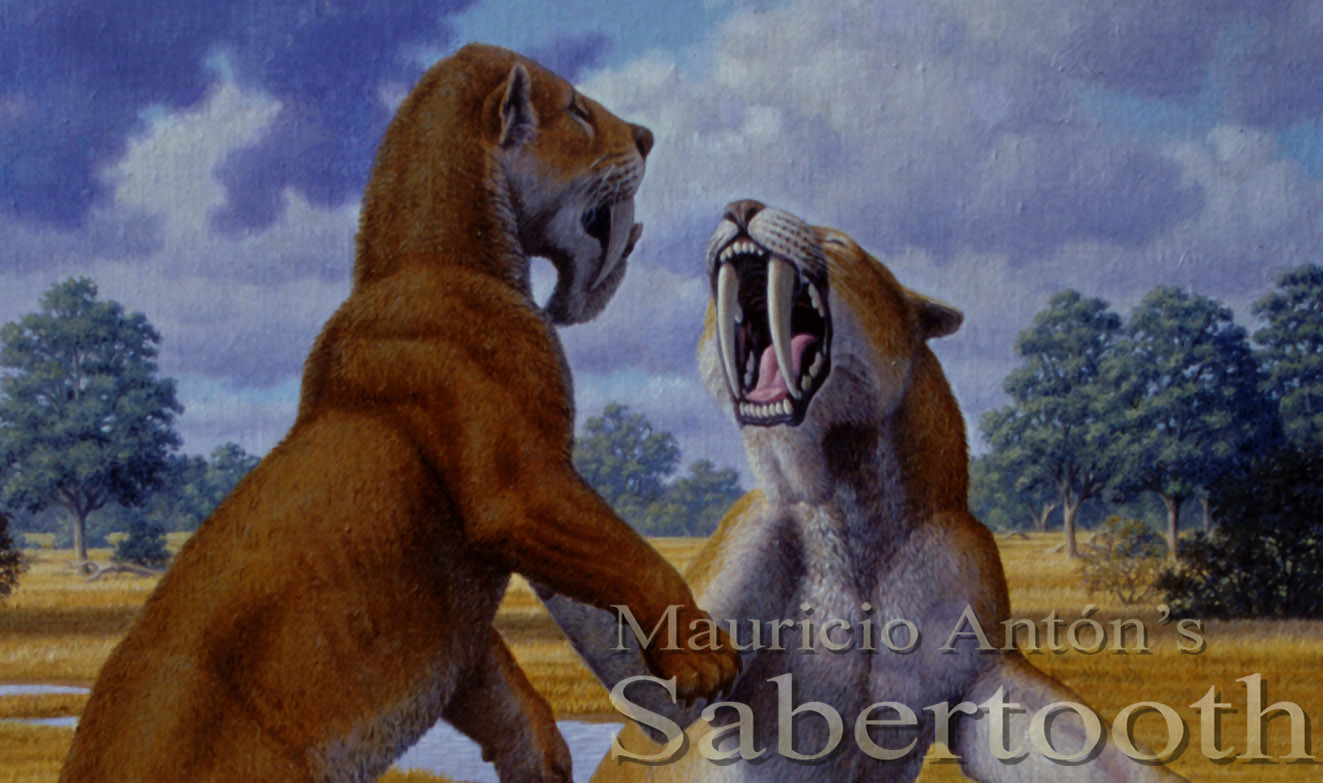

Eusmilus sicarius was a comparatively small sabertooth, about the size of a large lynx or a small leopard. It resembles a small, long bodied and short legged leopard. Here are series of images by Mauricio Anton:

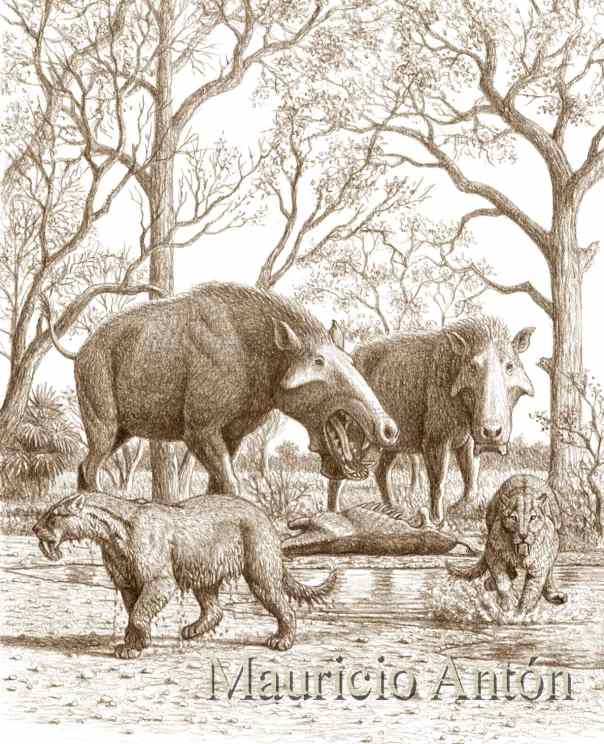

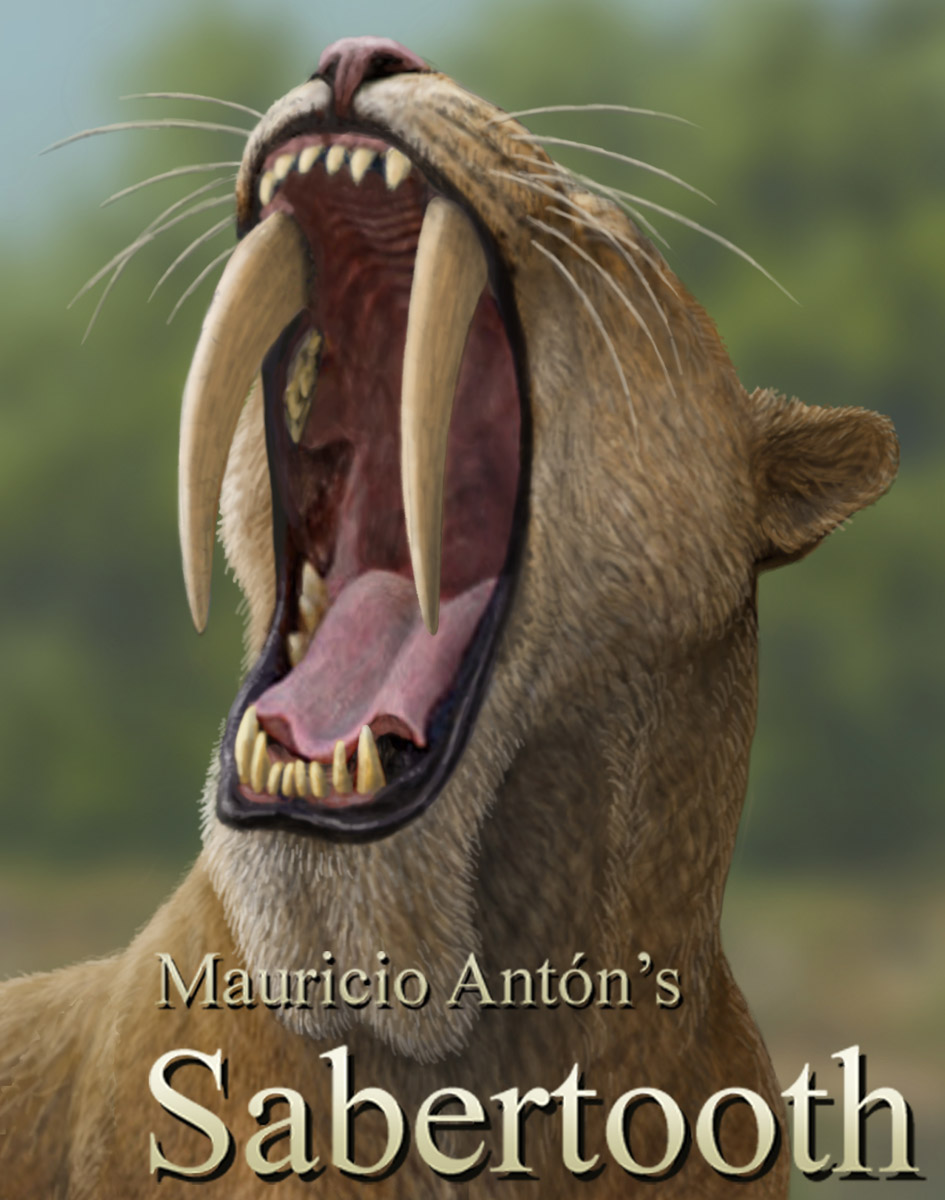

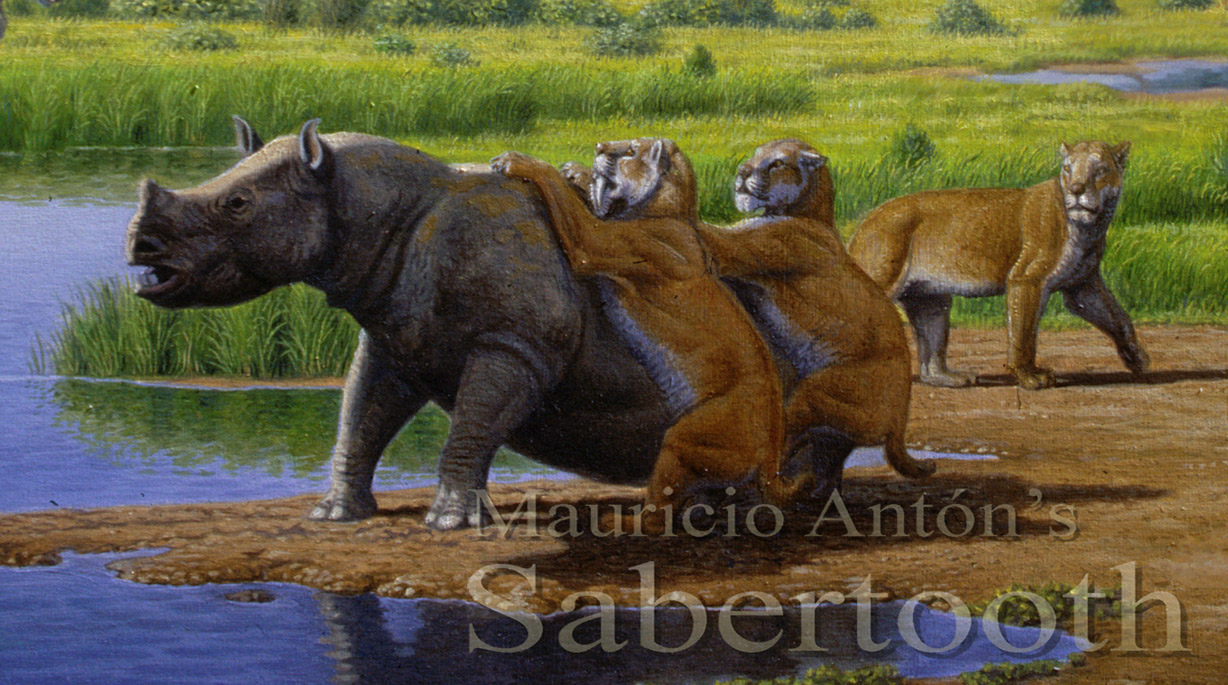

Barbourofelis fricki was a large animal, about the size of a lion. It actually ressembles Smilodon, especially S. populator, the first two reconstructions after the diagrams (images 4 and 5) in my earlier post. The other images are those of the smaller S. fatalis (of the La Brae tar pit fame). Like S. populator, it is a little more robust than the similar sized S. fatalis. The main difference is in the almost plantigrade stance of Barbourofelis as opposed to the digitigrade stance (standing on toes) of Smilodon and the presence of the protective flange on the lower jaw. So Chris, if you decide one day to do a sabertooth tiger, I hope you can do a morph of Barbourofelis as well (hint, hint). Here are a series of images by Mauricio Anton:

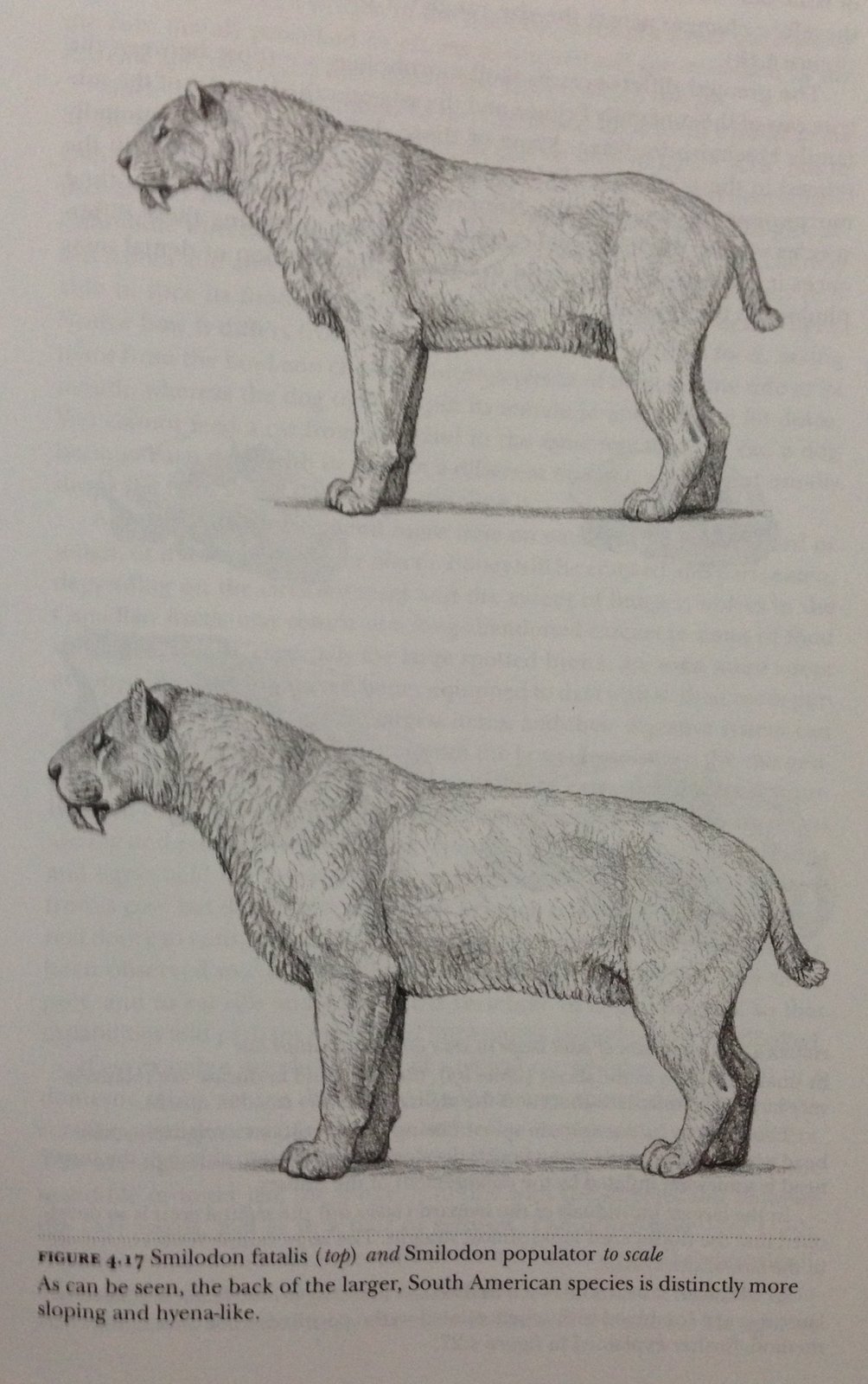

Lastly, a drawing showing the size difference between Smilodon populator and Smilodon fatalis and the resulting difference in relative proportions in the body.

Answer: When it belongs to the related families of Barbourofelidae and Nimravidae and not Felidae.

Barbourofelis fricki, a barbourofelid, and Eusmilus sicarius, a nimravid are two sabertooths with the most extreme sabertooth adaptation ever seen, even more so than Smilodon! Their canines are relatively longer than those of Smilodon so much so they have flanges on their mandibles to protect them. Their hind limbs are almost plantigrade so as to stabilise them when they pull down larger prey. They were both originally thought to be true cats and were at one time classified as cats in the family Felidae, the so called "Paleofelids". Later it was found that they had a different bone structure in the small bones of the ear. They were then placed in a new family, the Nimravidae. In the early 2000's, however, further studies indicate that the barbourfelids were actually closer related to the true cats than they were to the nimravids and so they (the barbourofilids) were placed in a family of their own, the Barbourofelidae.

Eusmilus sicarius was a comparatively small sabertooth, about the size of a large lynx or a small leopard. It resembles a small, long bodied and short legged leopard. Here are series of images by Mauricio Anton:

Barbourofelis fricki was a large animal, about the size of a lion. It actually ressembles Smilodon, especially S. populator, the first two reconstructions after the diagrams (images 4 and 5) in my earlier post. The other images are those of the smaller S. fatalis (of the La Brae tar pit fame). Like S. populator, it is a little more robust than the similar sized S. fatalis. The main difference is in the almost plantigrade stance of Barbourofelis as opposed to the digitigrade stance (standing on toes) of Smilodon and the presence of the protective flange on the lower jaw. So Chris, if you decide one day to do a sabertooth tiger, I hope you can do a morph of Barbourofelis as well (hint, hint). Here are a series of images by Mauricio Anton:

Lastly, a drawing showing the size difference between Smilodon populator and Smilodon fatalis and the resulting difference in relative proportions in the body.

Flint_Hawk

Dances with Bees

Laurie's White Tigers are in the store!

And they are in my cart!