-

Welcome to the Community Forums at HiveWire 3D! Please note that the user name you choose for our forum will be displayed to the public. Our store was closed as January 4, 2021. You can find HiveWire 3D and Lisa's Botanicals products, as well as many of our Contributing Artists, at Renderosity. This thread lists where many are now selling their products. Renderosity is generously putting products which were purchased at HiveWire 3D and are now sold at their store into customer accounts by gifting them. This is not an overnight process so please be patient, if you have already emailed them about this. If you have NOT emailed them, please see the 2nd post in this thread for instructions on what you need to do

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Songbird Remix's Product Preview Thread

- Thread starter Ken Gilliland

- Start date

Mythocentric

Extraordinary

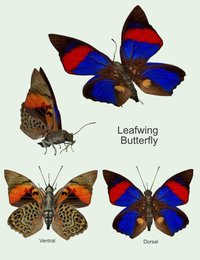

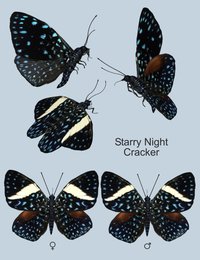

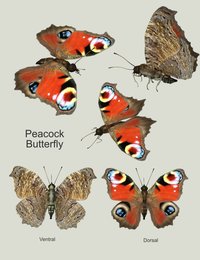

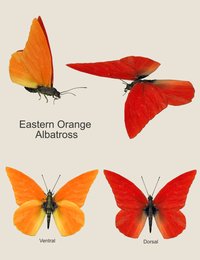

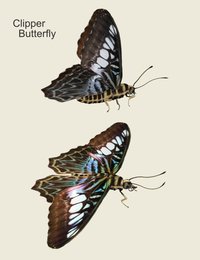

I waited a long time hoping Ken would turn his mind to butterflies, and boy, were they worth waiting for! Ken always goes above and beyond the call of duty to produce something extraordinary!

Here's a sneak peak at my next set, "Flowerpiercers and Leaftossers", two species of South American birds.

Here's the Moustached Flowerpiercer with some aracari (toucans) flying in the background

Here's the Moustached Flowerpiercer with some aracari (toucans) flying in the background

Not really... Flowerpiercers may punch a hole near the base of a flower to gets its nectar, but leaftossers simply toss leaves on the ground hunting for bugs.

Why these birds? I found the names fun (sort of like my "spiderhunters"), so I couldn't resist... Just thinking about doing an image with a bird called a "Tawny-breasted Leaftosser" makes me giggle a little.

An Indigo Flowerpiercer with a Tawny-breasted Leaftosser (up on the limb) checking out his forage area.

Why these birds? I found the names fun (sort of like my "spiderhunters"), so I couldn't resist... Just thinking about doing an image with a bird called a "Tawny-breasted Leaftosser" makes me giggle a little.

An Indigo Flowerpiercer with a Tawny-breasted Leaftosser (up on the limb) checking out his forage area.

Rather OT but I was just browsing a tumblr account that I look in on fairly often, and somebody reposted a video regarding the Hooded Pitohui, which I gather is a poisonous bird. Its feathers give off the same neurotoxin as poison dart frogs. I gather they are corvids. Very colorful for corvids, too.

Interesting bird... I may have to do that species eventually

My "Flowerpiercers & Leaftossers" is out today.

In a few weeks, expect a fourth installment in the "Threatened Endangered Extinct", in time for Audubon's birthday. This set will have a good variety of birds ranging from the extinct Labrador Duck to threatened stunners like the Banded Cotinga and Scaly Ground-roller

In a few weeks, expect a fourth installment in the "Threatened Endangered Extinct", in time for Audubon's birthday. This set will have a good variety of birds ranging from the extinct Labrador Duck to threatened stunners like the Banded Cotinga and Scaly Ground-roller

Attachments

A sneak peak at some of the cast in my upcoming "Threatened Endangered Extinct v4".

Here is the Labrador Duck. It was a sea duck that migrated annually, wintering off the coasts of New Jersey and New England in the eastern United States, where it favored southern sandy coasts, sheltered bays, harbors, and inlets, and breeding in Labrador and northern Quebec in the summer.

It has the distinction of being the first known endemic North American bird species to become extinct after the Columbian Exchange, with the last known sighting occurring in 1878 in Elmira, New York. The Labrador duck is thought to have been always rare, but between 1850 and 1870, populations waned further. Its extinction (sometime after 1878) is still not fully explained. Although hunted for food, this duck was considered to taste bad, rotted quickly, and fetched a low price. Consequently, it was not sought much by hunters. However, the eggs may have been over-harvested, and it may have been subject to depredations by the feather trade in its breeding area, as well. Another possible factor in the bird's extinction was the decline in mussels and other shellfish on which they are believed to have fed in their winter quarters, due to growth of population and industry on the Eastern Seaboard. Although all sea ducks readily feed on shallow-water molluscs, no Western Atlantic bird species seems to have been as dependent on such food as the Labrador duck.

Another theory that was said to lead to their extinction was a huge increase of human influence on the coastal ecosystems in North America, causing the birds to flee their niches and find another habitat. These ducks were the only birds whose range was limited to the American coast of the North Atlantic, so changing niches was a difficult task. Whatever the causes may be, the Labrador duck became extinct in the late 19th century.

The Labrador duck has been considered the most enigmatic of all North American birds. There are 55 specimens of the Labrador duck preserved in museum collections worldwide.

Author Glen Chilton investigated the wherabouts of every known specimen scattered amongst the museums of Europe, North America, and the Middle East, and wrote an captivating book about his search called “The Curse of the Labrador Duck”.

Here is the Labrador Duck. It was a sea duck that migrated annually, wintering off the coasts of New Jersey and New England in the eastern United States, where it favored southern sandy coasts, sheltered bays, harbors, and inlets, and breeding in Labrador and northern Quebec in the summer.

It has the distinction of being the first known endemic North American bird species to become extinct after the Columbian Exchange, with the last known sighting occurring in 1878 in Elmira, New York. The Labrador duck is thought to have been always rare, but between 1850 and 1870, populations waned further. Its extinction (sometime after 1878) is still not fully explained. Although hunted for food, this duck was considered to taste bad, rotted quickly, and fetched a low price. Consequently, it was not sought much by hunters. However, the eggs may have been over-harvested, and it may have been subject to depredations by the feather trade in its breeding area, as well. Another possible factor in the bird's extinction was the decline in mussels and other shellfish on which they are believed to have fed in their winter quarters, due to growth of population and industry on the Eastern Seaboard. Although all sea ducks readily feed on shallow-water molluscs, no Western Atlantic bird species seems to have been as dependent on such food as the Labrador duck.

Another theory that was said to lead to their extinction was a huge increase of human influence on the coastal ecosystems in North America, causing the birds to flee their niches and find another habitat. These ducks were the only birds whose range was limited to the American coast of the North Atlantic, so changing niches was a difficult task. Whatever the causes may be, the Labrador duck became extinct in the late 19th century.

The Labrador duck has been considered the most enigmatic of all North American birds. There are 55 specimens of the Labrador duck preserved in museum collections worldwide.

Author Glen Chilton investigated the wherabouts of every known specimen scattered amongst the museums of Europe, North America, and the Middle East, and wrote an captivating book about his search called “The Curse of the Labrador Duck”.

Another "Threatened Endangered Extinct v4" preview... this time the endangered Banded Cotingas.

It occurs in southeastern Bahia (in Brazil), with two records from northeast Minas Gerais in 2003 (Santa Maria do Salto and Bandeira municipalities) and none since the 19th century in Rio de Janeiro, south-east Brazil. It was previously easily observed in Espírito Santo, but there have been few, if any, records from the state since the 1990s and it may now be extirpated from the state. It has declined significantly in abundance and distribution and is now mostly confined to a few protected areas, notably RPPN Estação Veracel (formerly known as Estação Veracruz), Porto Seguro, Bahia as well as Reserva Serra Bonita, Camacan, also in Bahia.

There are 50-249 mature individuals left with a decreasing population trend. The main threats to the species are the large-scale destruction of the remaining lowland Atlantic forest and illegal capture for the cage-bird trade. The extensive and continuing deforestation within its range has isolated populations in a few key protected areas. Forest is logged and burned and cleared for conversion to agriculture for crops such as coffee and for grazing. In the past, birds were collected for feather-flower craftwork by local Indians and Bahian nuns. The apparent scarcity of the species in trade during recent decades is probably a consequence of its rarity.

It is a strikingly beautiful, dark blue cotinga. The male has bright, dark cobalt-blue upper-parts, somewhat mottled black on back. The female is dusky brown above scaled whitish. It has slightly paler and buffier under-parts with quite broad scaling, giving a paler appearance.

They eat fruit - predominantly Byrsonima sericea and Ficus species.

It occurs in southeastern Bahia (in Brazil), with two records from northeast Minas Gerais in 2003 (Santa Maria do Salto and Bandeira municipalities) and none since the 19th century in Rio de Janeiro, south-east Brazil. It was previously easily observed in Espírito Santo, but there have been few, if any, records from the state since the 1990s and it may now be extirpated from the state. It has declined significantly in abundance and distribution and is now mostly confined to a few protected areas, notably RPPN Estação Veracel (formerly known as Estação Veracruz), Porto Seguro, Bahia as well as Reserva Serra Bonita, Camacan, also in Bahia.

There are 50-249 mature individuals left with a decreasing population trend. The main threats to the species are the large-scale destruction of the remaining lowland Atlantic forest and illegal capture for the cage-bird trade. The extensive and continuing deforestation within its range has isolated populations in a few key protected areas. Forest is logged and burned and cleared for conversion to agriculture for crops such as coffee and for grazing. In the past, birds were collected for feather-flower craftwork by local Indians and Bahian nuns. The apparent scarcity of the species in trade during recent decades is probably a consequence of its rarity.

It is a strikingly beautiful, dark blue cotinga. The male has bright, dark cobalt-blue upper-parts, somewhat mottled black on back. The female is dusky brown above scaled whitish. It has slightly paler and buffier under-parts with quite broad scaling, giving a paler appearance.

They eat fruit - predominantly Byrsonima sericea and Ficus species.

Here's another preview of my "Threatened Endangered Extinct v4" set, this time showing the "Vulnerable" Southern Bald Ibis from southern Africa. It will be released on Audubon's birthday.

The Southern Bald Ibis is restricted to Lesotho, north-east South Africa and west Swaziland. The core range lies in the north-eastern Free State, Mpumalanga and the KwaZulu-Natal Drakensberg.

There are only 3,300-4,000 mature individuals left with a decreasing population trend. Overall, the species's population is suspected to have decreased at a moderate rate because of habitat loss and degradation (commercial afforestation, intensive crop farming, open-cast mining, acid rain and dense human settlement). Population declines are projected to occur in the future if current rates of habitat loss continue and due to climate change.

Their diet is composed mainly of insects and other small invertebrates found in burnt grasslands. The southern bald ibis is known to be a relatively quiet bird. This species in particular has been noted to make a weak gobbling sound. This is refers back to their old Afrikaans name of “Wilde-Kalkoen”, otherwise translated as “wild turkey”. This bird is most boisterous in the nesting areas and in flight. It projects a high-pitched keeaaw-klaup-klaup call, resembling that of a turkeys.

The Southern Bald Ibis is restricted to Lesotho, north-east South Africa and west Swaziland. The core range lies in the north-eastern Free State, Mpumalanga and the KwaZulu-Natal Drakensberg.

There are only 3,300-4,000 mature individuals left with a decreasing population trend. Overall, the species's population is suspected to have decreased at a moderate rate because of habitat loss and degradation (commercial afforestation, intensive crop farming, open-cast mining, acid rain and dense human settlement). Population declines are projected to occur in the future if current rates of habitat loss continue and due to climate change.

Their diet is composed mainly of insects and other small invertebrates found in burnt grasslands. The southern bald ibis is known to be a relatively quiet bird. This species in particular has been noted to make a weak gobbling sound. This is refers back to their old Afrikaans name of “Wilde-Kalkoen”, otherwise translated as “wild turkey”. This bird is most boisterous in the nesting areas and in flight. It projects a high-pitched keeaaw-klaup-klaup call, resembling that of a turkeys.

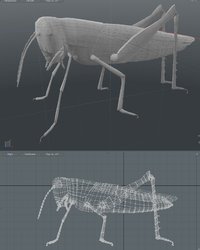

It's about time we had grasshoppers. Good idea. The birds need a more varied diet.

Speaking of Audobon, the Cake Wrecks sunday sweets have done another presentation of fabulous bird cakes for the occasion.

Cake Wrecks

Speaking of Audobon, the Cake Wrecks sunday sweets have done another presentation of fabulous bird cakes for the occasion.

Cake Wrecks

great looking cakes

I figure the model will yield grasshoppers, crickets and locusts with a robust group of morphs... and with a hybrid model (based on it) I'm thinking a Jerusalem cricket (aka Potato bug).

I figure the model will yield grasshoppers, crickets and locusts with a robust group of morphs... and with a hybrid model (based on it) I'm thinking a Jerusalem cricket (aka Potato bug).

Happy Earth Day... Edward Abbey (American author and essayist) wrote "Wilderness is not a luxury but a necessity of the human spirit, as vital to our lives as water and bread." It's easy for me to understand this this morning as I watch seven separate bird species making and tending nests around our house in the garden; Oak Titmice, Nuttall's Woodpeckers, Western Bluebirds. Acorn Woodpeckers, Bushtits, Allen's and Anna's Hummingbirds. It's quite the bird show this year... and Nature never fails to entertain and amaze. One of our secrets is planting endemic native plants... These plants entice native insects and in turn, attract birds... if you build it, they will come.

Okay, about today's image for Threatened, Endangered Extinct v4 (to be released on Audubon's birthday April 26)... the Critically Endangered Guam Rail.

As expected, the Guam rail is endemic to Guam. It was found more frequently in savannas and scrubby mixed forest than in uniform tracts of mature forest. It was usually found in dense vegetation but it was also observed bathing or feeding along roadsides or forest edges.

The species was formerly extinct in the wild and an introduced population has now been established on Cocos, where 16 individuals were released in 2010 and a further 10 in 2012. Although individuals have been released on Guam and on Rota, there are unlikely to be any wild individuals remaining on Guam and the population on Rota is not yet considered to be self-sustaining. Evidence for breeding has been observed and the bird is now found throughout the island, so the population size is suspected to be increasing (up to 50).

The species was once abundant, with an estimated population to be around 70,000 before the 1960s. It evolved in the absence of predators, such as snakes and rats, and might have been more abundant before American colonization. After the end of World War II, the brown tree snake was accidentally transported from its native range in Papua New Guinea to Guam, probably as a stowaway in military ship cargo. Beginning in the 1960s, the snake became well established as numbers began to grow exponentially, and the rail populations subsequently plummeted, along with the rest of Guam's native bird populations. The Guam rail had no experience with such a predator, and lacked protective behaviors against the snake. Consequently, it was an easy prey for this efficient, nocturnal predator.

Appreciable losses of the Guam rail was not evident until the mid 1960s. By 1963, several formerly abundant rails had disappeared from the central part of the island where snakes were most populous. By the late 1960s, it had begun to decline in the central and southern parts of the island, and remained abundant only in isolated patches of forest on the northern end of the island. Snakes began affecting the rail in the north-central and extreme northern parts of the island in the 1970s and 1980s, respectively. The population declined severely from 1969 to 1973, and continued to decline until the mid 1980s. It was last seen in the wild in 1987. Other significant threats to the rail include habitat destruction, predation by introduced rats, feral cats, and pigs.

It is omnivorous, but appears to prefer animal over vegetable food. It is known to eat gastropods (slugs and snails), skinks, geckos, insects, and carrion, as well as seeds and palm leaves. It is a secretive bird and it can run rapidly. Though its capable of a short bursts of flight, the bird seldom flies.

It is known locally as the ko'ko' bird. Its call is a loud, piercing whistle or series of whistles, usually given by two or more birds in response to a loud noise, the call of another rail, or other disturbances.

Okay, about today's image for Threatened, Endangered Extinct v4 (to be released on Audubon's birthday April 26)... the Critically Endangered Guam Rail.

As expected, the Guam rail is endemic to Guam. It was found more frequently in savannas and scrubby mixed forest than in uniform tracts of mature forest. It was usually found in dense vegetation but it was also observed bathing or feeding along roadsides or forest edges.

The species was formerly extinct in the wild and an introduced population has now been established on Cocos, where 16 individuals were released in 2010 and a further 10 in 2012. Although individuals have been released on Guam and on Rota, there are unlikely to be any wild individuals remaining on Guam and the population on Rota is not yet considered to be self-sustaining. Evidence for breeding has been observed and the bird is now found throughout the island, so the population size is suspected to be increasing (up to 50).

The species was once abundant, with an estimated population to be around 70,000 before the 1960s. It evolved in the absence of predators, such as snakes and rats, and might have been more abundant before American colonization. After the end of World War II, the brown tree snake was accidentally transported from its native range in Papua New Guinea to Guam, probably as a stowaway in military ship cargo. Beginning in the 1960s, the snake became well established as numbers began to grow exponentially, and the rail populations subsequently plummeted, along with the rest of Guam's native bird populations. The Guam rail had no experience with such a predator, and lacked protective behaviors against the snake. Consequently, it was an easy prey for this efficient, nocturnal predator.

Appreciable losses of the Guam rail was not evident until the mid 1960s. By 1963, several formerly abundant rails had disappeared from the central part of the island where snakes were most populous. By the late 1960s, it had begun to decline in the central and southern parts of the island, and remained abundant only in isolated patches of forest on the northern end of the island. Snakes began affecting the rail in the north-central and extreme northern parts of the island in the 1970s and 1980s, respectively. The population declined severely from 1969 to 1973, and continued to decline until the mid 1980s. It was last seen in the wild in 1987. Other significant threats to the rail include habitat destruction, predation by introduced rats, feral cats, and pigs.

It is omnivorous, but appears to prefer animal over vegetable food. It is known to eat gastropods (slugs and snails), skinks, geckos, insects, and carrion, as well as seeds and palm leaves. It is a secretive bird and it can run rapidly. Though its capable of a short bursts of flight, the bird seldom flies.

It is known locally as the ko'ko' bird. Its call is a loud, piercing whistle or series of whistles, usually given by two or more birds in response to a loud noise, the call of another rail, or other disturbances.

Last edited:

Flint_Hawk

Dances with Bees

What a wonderful selection of birds you have!

So far this morning we have had Lesser Goldfinch, House Finch, House Sparrow, Eurasian Collared-dove & European Starlings visit our feeders. The Lesser Goldfinch have claimed a group of cedars as their home. If something startles them, they spew out of those cedars like a volcano erupting! It is quite a sight! We are lucky enough to live at the base of a hill that is covered with native plants.

So far this morning we have had Lesser Goldfinch, House Finch, House Sparrow, Eurasian Collared-dove & European Starlings visit our feeders. The Lesser Goldfinch have claimed a group of cedars as their home. If something startles them, they spew out of those cedars like a volcano erupting! It is quite a sight! We are lucky enough to live at the base of a hill that is covered with native plants.

Last edited: