Yes, I understand and I do realize it probably would sell well and be popular... but there's too many real birds out there that need me to create them so they aren't forgotten and slip away into extinction.Mechanical/Steampunk birds are a thing...

-

Welcome to the Community Forums at HiveWire 3D! Please note that the user name you choose for our forum will be displayed to the public. Our store was closed as January 4, 2021. You can find HiveWire 3D and Lisa's Botanicals products, as well as many of our Contributing Artists, at Renderosity. This thread lists where many are now selling their products. Renderosity is generously putting products which were purchased at HiveWire 3D and are now sold at their store into customer accounts by gifting them. This is not an overnight process so please be patient, if you have already emailed them about this. If you have NOT emailed them, please see the 2nd post in this thread for instructions on what you need to do

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Songbird Remix's Product Preview Thread

- Thread starter Ken Gilliland

- Start date

A couple things... two updates to my products are now live at my Renderosity store.

First, my Wings for the HW Horse have been updated so that they perform better with the current versions of Iray and Superfly. I slightly changed some settings and added a morph that corrects Physical Renderer issues.

Second, the update for one of my popular sets is finally done, Songbird ReMix Second Edition.

Second Edition has had a confusing history. It originally started as an upgrade to Songbird ReMix and was originally called "Songbird ReMix2". After creating a few sets after it, customers became confused as to exactly what was required to make each set work, so I ended up scrapping all the requirements and made every set standalone. "Songbird ReMix2" was renamed to "Second Edition".

Since then, there's no more confusion but two sets have suffered all those years; Songbird ReMix and Second Edition. Both had been light on content because they originally contained "Required" models.

When I started updating the series for Superfly and Iray, I decided it was time to even out those two sets. The original Songbird ReMix set had 7 more birds added to it and my newly re-released, Second Edition, has 12 new birds and two props added to the set.

What's been added? 1 new Rock Pigeon, female versions of the Anna's and Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, female versions of the Kookaburras (as well as "Little" Laughing Kookaburra subspecies), male and female versions of two Lesser Goldfinch subspecies, a thistle sock and a "Don't Feed the Pigeons" sign.

First, my Wings for the HW Horse have been updated so that they perform better with the current versions of Iray and Superfly. I slightly changed some settings and added a morph that corrects Physical Renderer issues.

Second, the update for one of my popular sets is finally done, Songbird ReMix Second Edition.

Second Edition has had a confusing history. It originally started as an upgrade to Songbird ReMix and was originally called "Songbird ReMix2". After creating a few sets after it, customers became confused as to exactly what was required to make each set work, so I ended up scrapping all the requirements and made every set standalone. "Songbird ReMix2" was renamed to "Second Edition".

Since then, there's no more confusion but two sets have suffered all those years; Songbird ReMix and Second Edition. Both had been light on content because they originally contained "Required" models.

When I started updating the series for Superfly and Iray, I decided it was time to even out those two sets. The original Songbird ReMix set had 7 more birds added to it and my newly re-released, Second Edition, has 12 new birds and two props added to the set.

What's been added? 1 new Rock Pigeon, female versions of the Anna's and Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, female versions of the Kookaburras (as well as "Little" Laughing Kookaburra subspecies), male and female versions of two Lesser Goldfinch subspecies, a thistle sock and a "Don't Feed the Pigeons" sign.

Last edited:

I have just read an article on superprecociality in pterosaurs whereby baby pterosaurs could fly immediately after hatching and even occupy different niches from their parents. It occurred to me that there is one group of modern birds that could do just that! They do not incubate their eggs with their body heat like other birds, but bury their eggs under massive nest mounds of decaying vegetation. Neither do they brood their young with body heat after hatching (other precocial chicks are not independent in thermoregulation and are unable to regulate their own body temperatures and so require parental brooding). In fact they are left on their own to hatch, dig themselves out of the nest (in the manner of newly hatched turtles) and immediately fend for themselves. I thought I should introduce this remarkable group of birds as well as the concept of precociality to this forum. These birds are the Megapodes.

Megapodes are an interesting Australasian family of birds closely related to the Gamebirds (Galliformes). They are also known as incubator birds or mound-builders, and are stocky, medium to large, chicken-like birds with small heads and large feet in the family Megapodiidae. Bird hatchlings, like new-born mammals, can be precocial where the young are relatively mature and mobile from the moment of birth or hatching. The opposite developmental strategy is called altricial, where the young are born or hatched helpless as in songbirds. Examples of precocial birds include the domestic chicken, many species of ducks and geese, waders and rails. Extremely precocial species are called "superprecocial". Megapodes are "superprecocial", hatching from their eggs in the most mature condition of any bird. They hatch with open eyes, bodily coordination and strength, full wing feathers, and downy body feathers, and are able to run, pursue prey, and in some species, fly on the same day they hatch. Megapodes do not incubate their eggs with their body heat as other birds do, but bury them. Their eggs are unusual in having a large yolk, making up 50 - 70% of the egg weight. The birds are best known for building massive nest mounds of decaying vegetation, which the male attends, adding or removing litter to regulate the internal heat while the eggs develop. However, some bury their eggs in other ways: there are burrow-nesters which use geothermal heat, and others which simply rely on the heat of the sun warming sand.

Nest Mounds and Nesting sites:

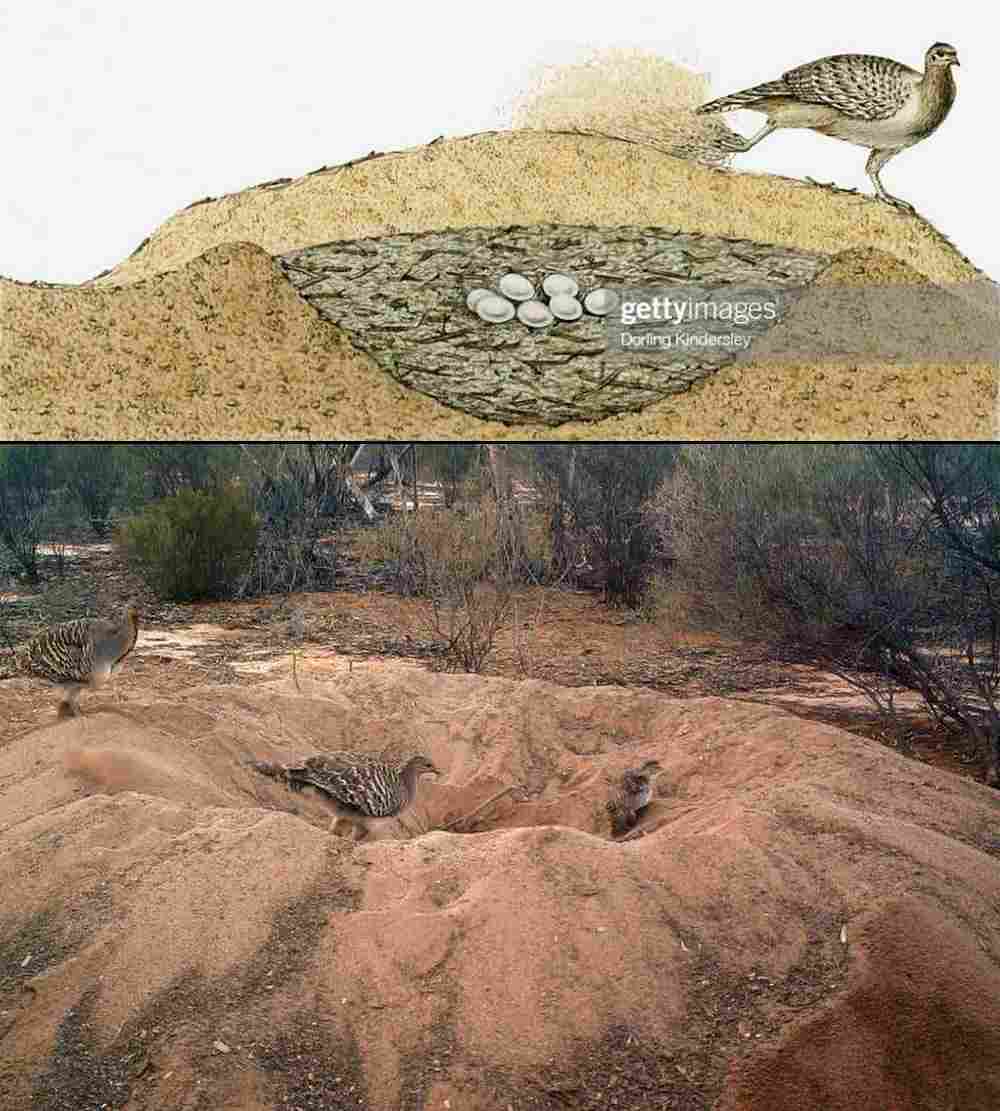

1. Top to bottom:

a. Malleefowl Nest Mound (Malleefowl nest mounds can be over 1m in height and 4m across. The male buries wet leaf litter in the mound, which gives off heat as it rots, acting as a natural incubator for the eggs. Throughout the breeding season, the male has to ensure that the temperature inside the mound is maintained at about 33°C. Temperature is maintained by digging the nest and by adding or removing sand).

b. Australian Brushturkey Nest Mound (They build large nests on the ground made of leaves, other compostable material, and earth, 1 to 1.5 metres high and up to 4 metres across. The eggs are hatched by the heat of the composting mound, the temperature of which is regulated by adding or removing material to maintain the temperature in the 33 to 35 °C incubation temperature range.The same nesting site is frequently used year after year).

c. Mound of the Orange-footed scrubfowl (Megapodius are best known for building a massive mound of decaying vegetation, which the male attends, adding or removing litter to regulate the internal heat while the eggs hatch)

2. Top to bottom:

a. Moluccan Scrubfowl burrows at nesting site (The nesting grounds are usually located in sun-exposed beach or volcanic soils.The Moluccan megapode is the only megapode known to lay its eggs nocturnally).

2. Close-up of Maleo nest.

3. Maleo Nesting Site (The Maleo is a mound builder that uses volcanic and solar-heated sand to incubate its eggs in large colonial nesting grounds).

3.Top to bottom:

a. Illustration of Malleefowl covering its Eggs with sand.

b. Pair of Malleefowls atop Nesting Mound.

Instead of a sharp dividing line between hatchlings that are precocial and those that are altricial, there is a gradient of precociality.

Precocial: There are four levels of precociality. Level 1 of development (precocial 1) is the pattern found in the chicks of megapodes (Australian Malee fowl, Brush Turkeys, etc.), which are totally independent of their parents ("superprecocial"). The megapode young are incubated in huge piles of decaying vegetation, and upon hatching dig their way out, already well feathered and able to fly. Precocial 2 development is found in ducklings and the chicks of shorebirds, which follow their parents but find their own food. The young of game birds, however, trail after their parents and are shown food; they are classified as precocial 3. Precocial 4 development is represented by the young of birds such as rails and grebes, which follow their parents and are not just shown food but are actually fed by them.

Semi-precocial: Hatched with eyes open, covered with down, and capable of leaving the nest soon after hatching (they can walk and often swim), but stay at the nest and are fed by parents. Basically precocial but nidicolus (young that remain in the nest), this developmental pattern is found in the young of gulls and terns.

Semi-altricial: Covered with down, incapable of departing from the nest, and fed by the parents. In species classified as semi-altricial 1, such as hawks and herons, chicks hatch with their eyes open. Owls, in the category semi-altricial 2, hatch with the eyes closed. If all young were divided into only two categories, altricial and precocial, these all would be considered altricial

Altricial: Hatched with eyes closed, with little or no down, incapable of departing from the nest, and fed by the parents. All passerines are altricial.

Megapodes are divided into 3 Groups:

1. Scrubfowl Group - 3 living genera

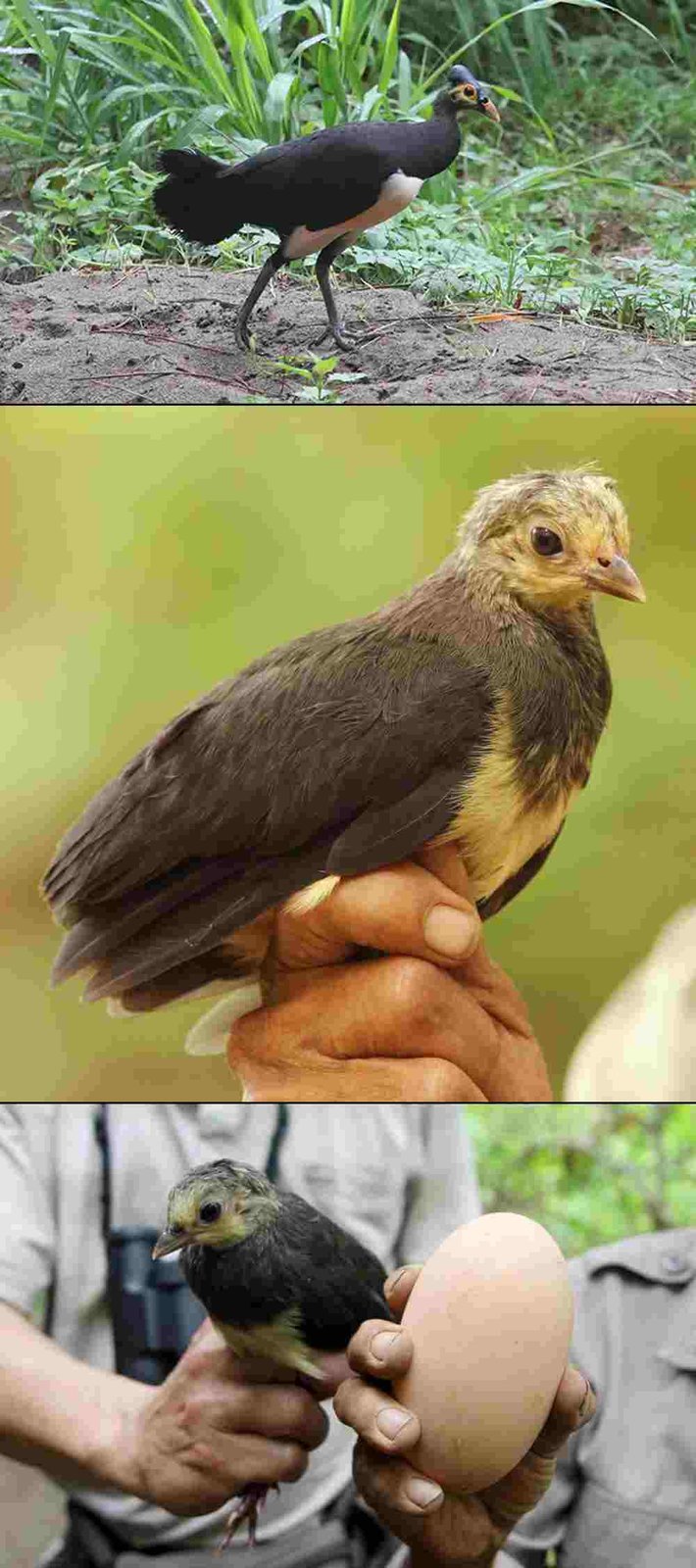

1a. Genus: Macrocephalon - 1 species, Maleo (Macrocephalon maleo).

Top to bottom:

a. Maleo (Macrocephalon maleo).

b. Hatchling. Note the fully formed flight feathers.

c. Comparative sizes of egg and newly hatched chick.

1b. Genus: Eulipoa - 1 species, Moluccan megapode (Eulipoa wallacei).

Top to bottom:

a. Moluccan scrubfowl (Eulipoa wallacei)

b. Moluccan scrubfowl in burrow laying eggs

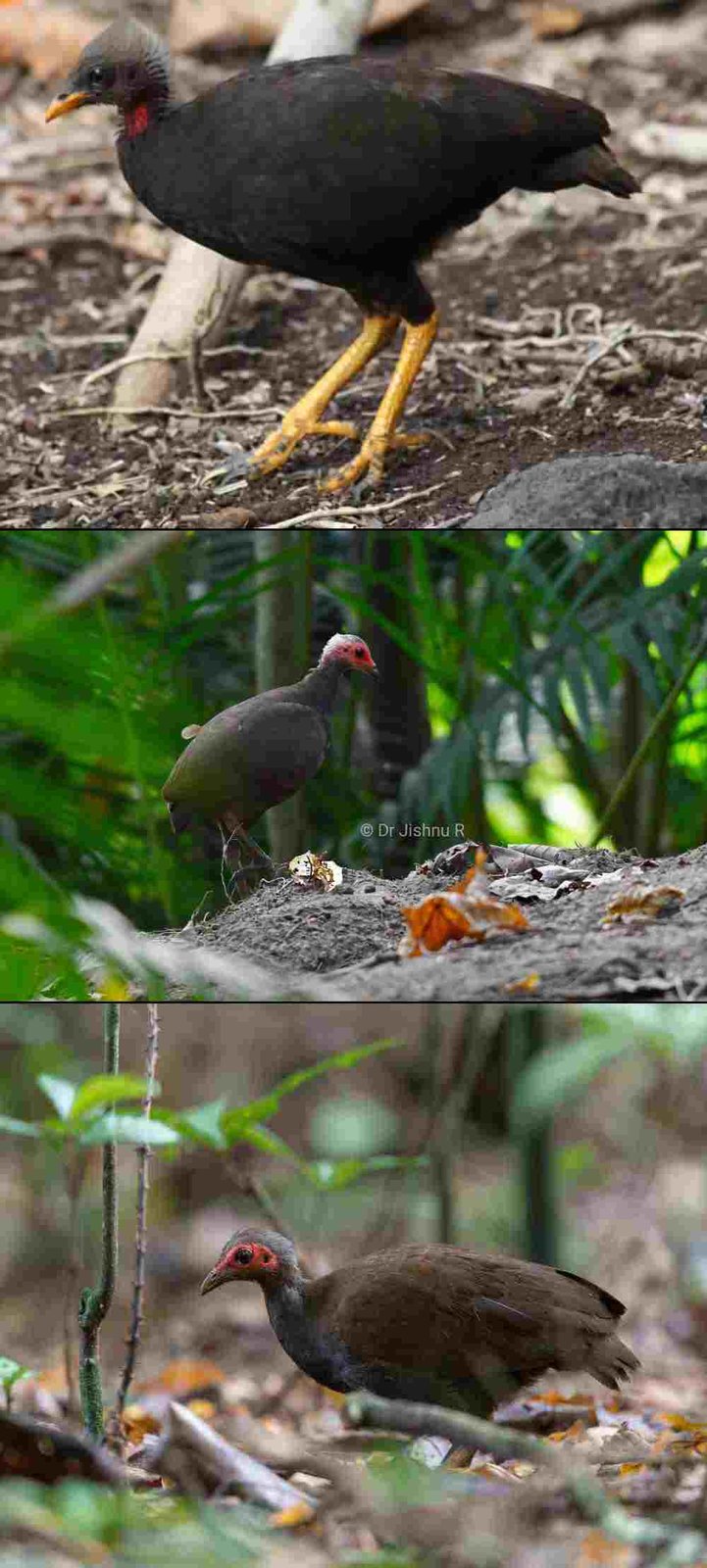

1c. Genus: Megapodius - 13 species.

Here are 3 examples:

Top to botttom:

a. Micronesian scrubfowl (Megapodius laperouse).

b. Nicobar scrubfowl (Megapodius nicobariensis).

c. Philippine scrubfowl (Megapodius cumingii).

Another 2 examples:

Top to botttom:

a. Tongan scrubfowl (Megapodius pritchardii).

b. Orange-footed scrubfowl (Megapodius reinwardt).

c. Orange-footed scrubfowl, juvenile with adult wing feathers.

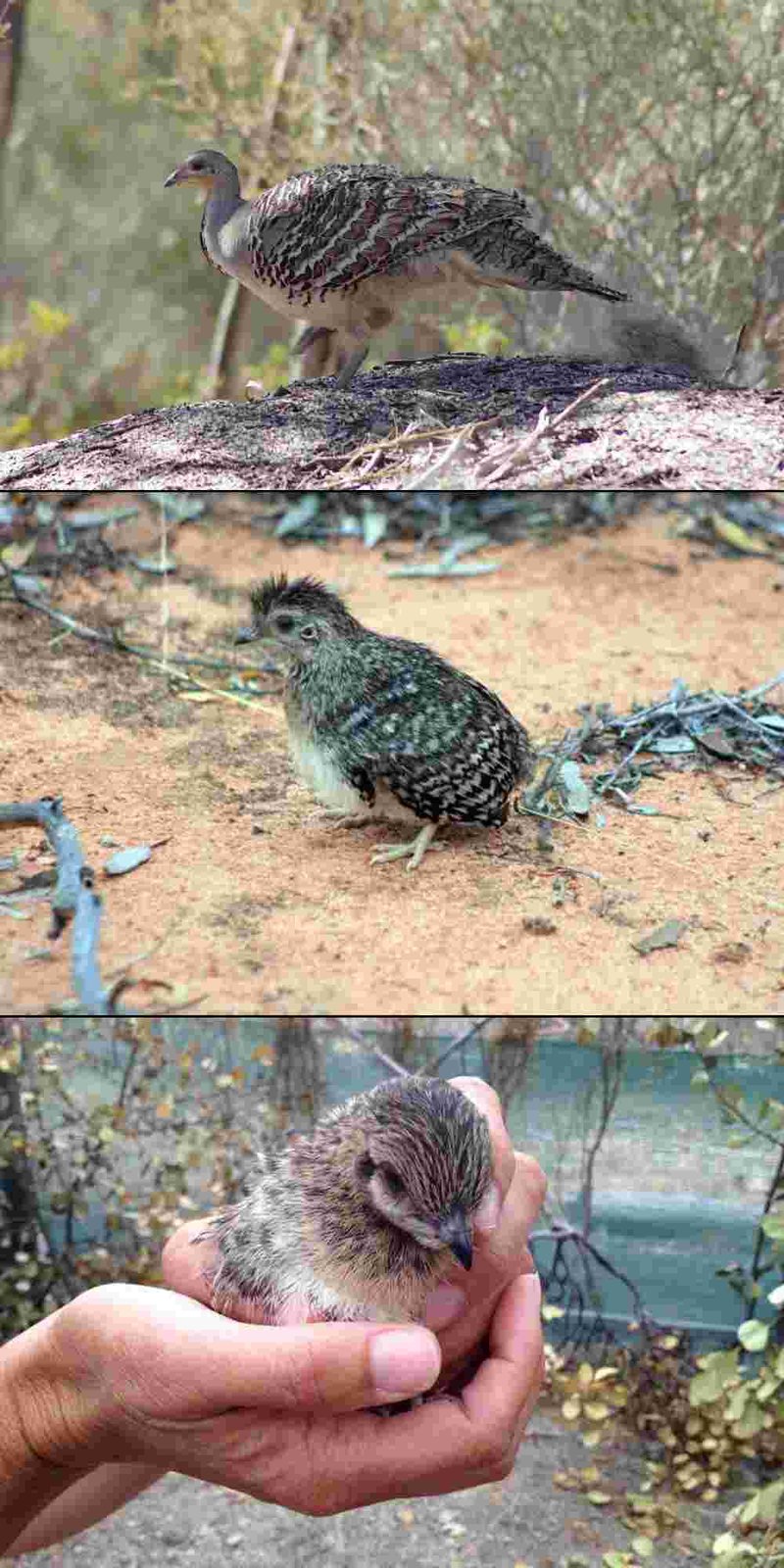

2. Malleefowl Group - 1 genus

2a. Genus: Leipoa - 1 species, Malleefowl (Leipoa ocellata)

Top to bottom:

a. Malleefowl (Leipoa ocellata).

b. Hatchling. Again, note the fully developed wing feathers.

c. Hatchling in hand.

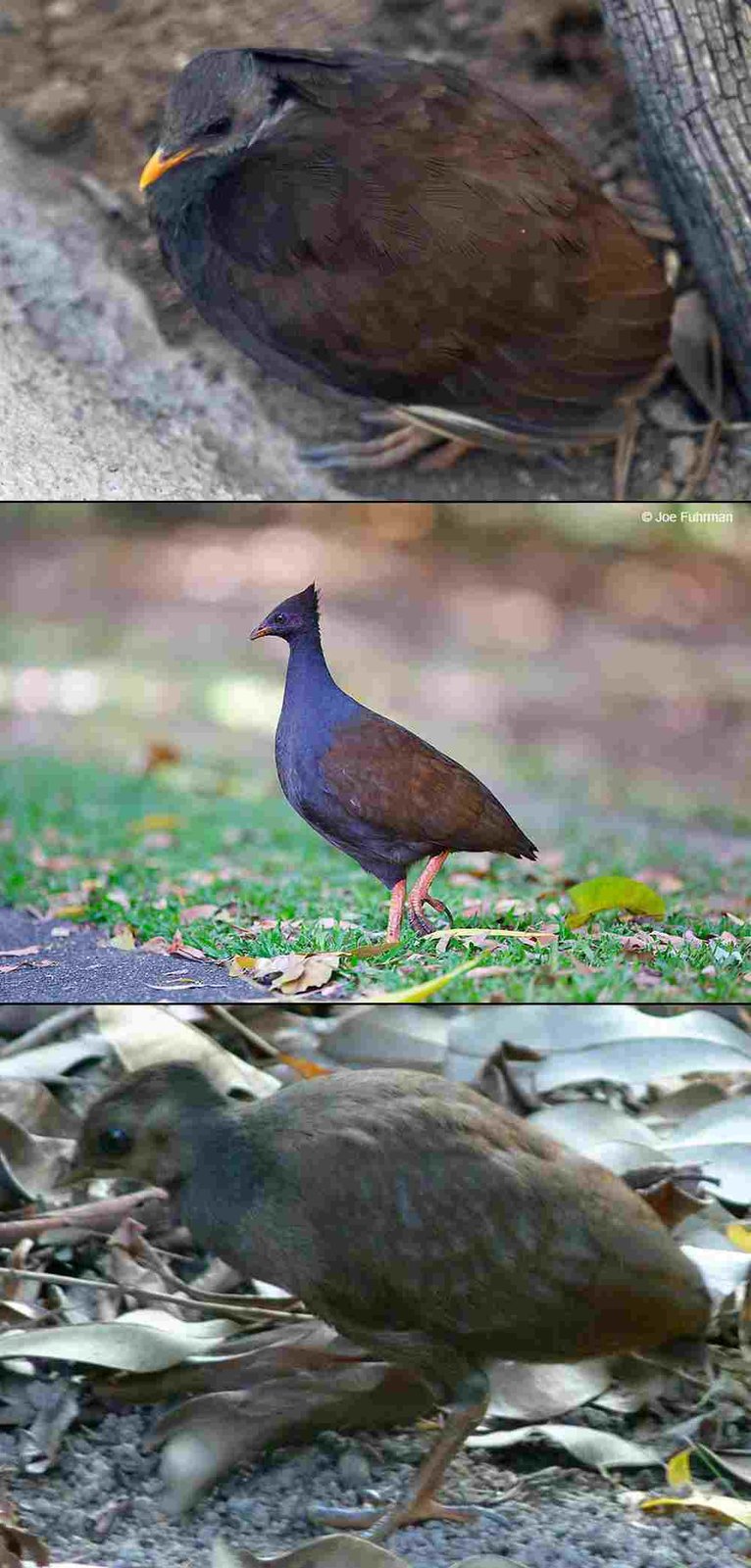

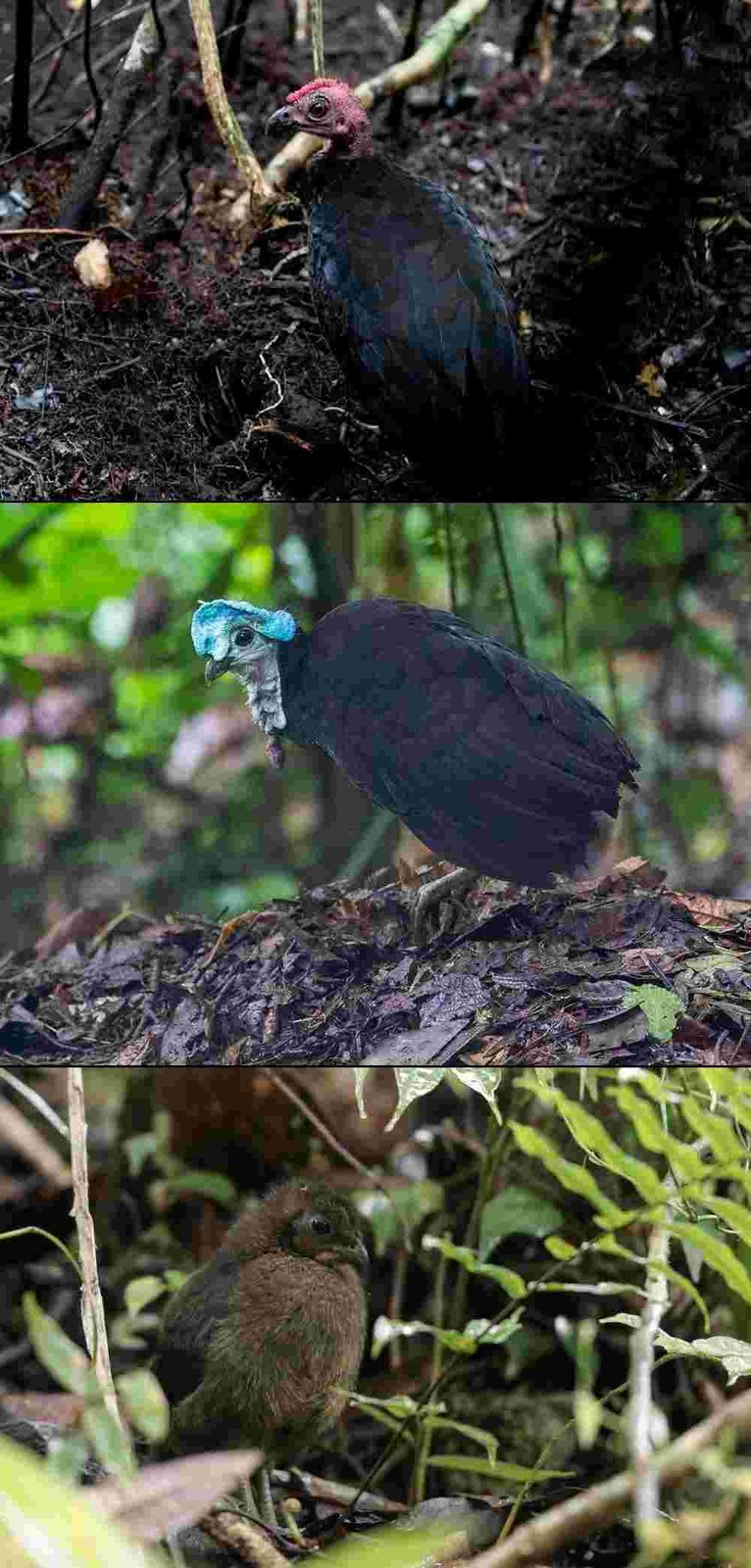

3. Brushturkey Group - 3 living genera

3a. Genus: Alectura - 1 species, Australian brushturkey (Alectura lathami)

Top to botttom:

a. Australian brushturkey (Alectura lathami).

b. Hatchling. Note the fully developed wing feathers.

c. Hatchling, showing wing feathers.

3b. Genus: Aepypodius - 2 species

Top to botttom:

a. Waigeo brushturkey ( Aepypodius bruijnii).

b. Wattled brushturkey (Aepypodius arfakianus).

c. Wattled brushturkey Hatchling.

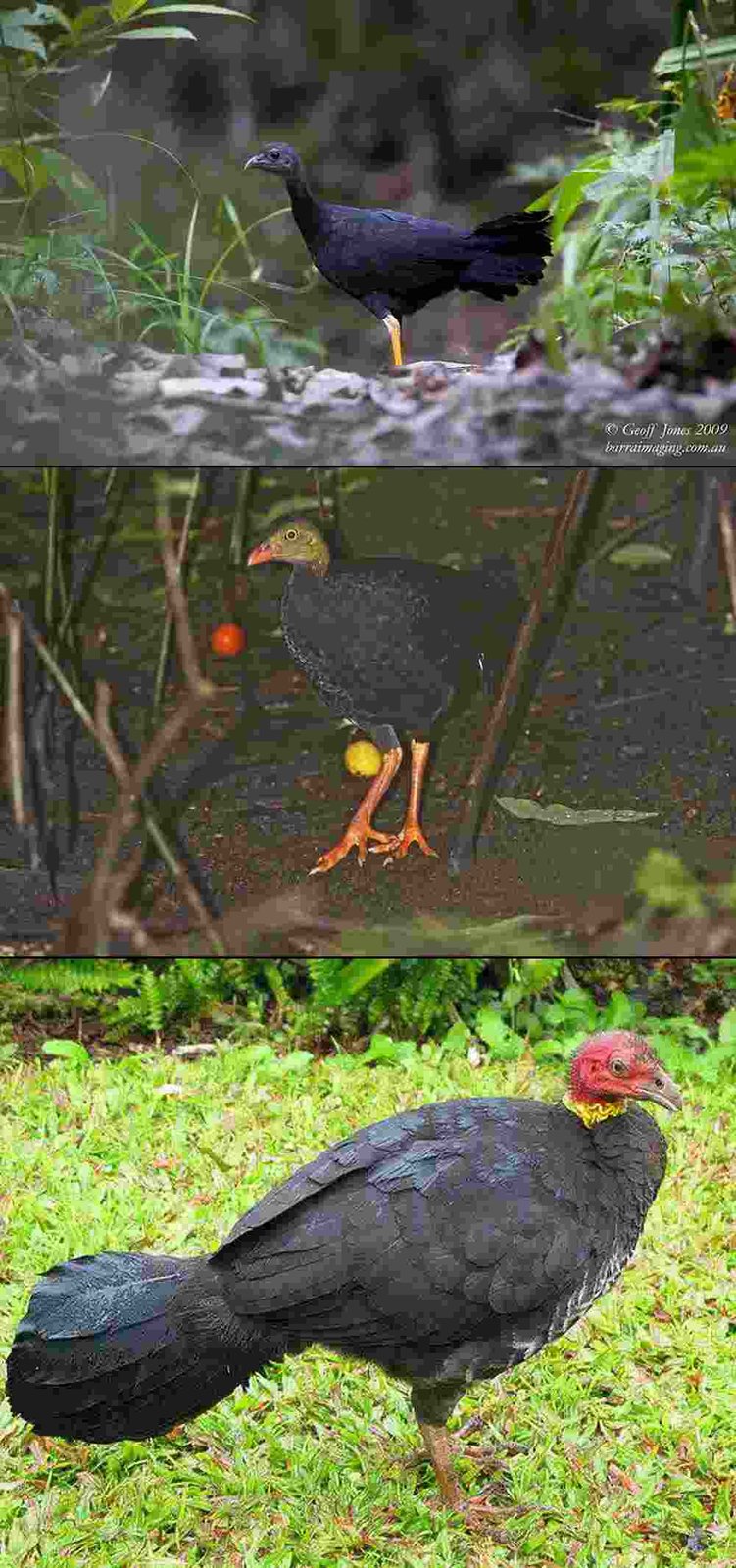

3c. Genus: Talegalla - 3 species

Top to bottom:

a. Black-billed brushturkey (Talegalla fuscirostris).

b. Red-billed brushturkey (Talegalla cuvieri).

c. Collared brushturkey (Talegalla jobiensis).

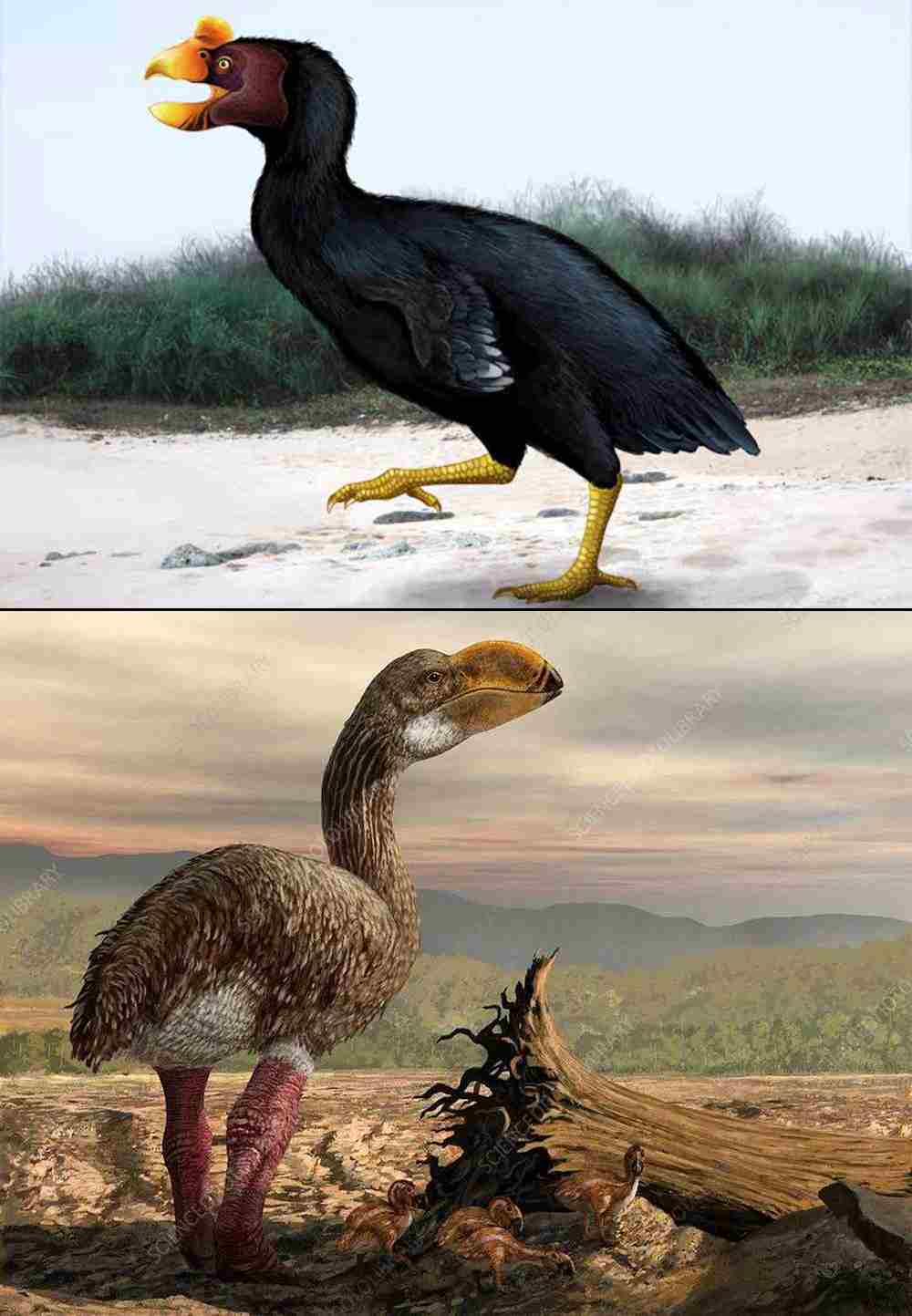

4. Extinct Giant Malleefowl

Top to bottom:

a. Progura gallinacea, the extinct Giant Mallee fowl.

b. Comparisons of skeletal elements of Progura gallinacea and Leipoa ocellata to indicate relative size .

Megapodes are the only extant birds with "superprecocial" chicks, which leave the nest immediately after hatching and do not receive any post-hatching parental care. Kiwi hatchlings likewise spend only a very short time in the nest and though not really "superprecocial" (they are advaced level 2 precocial), are more precocial than the young of most other extant birds. Kiwi chicks hatch as mini-adults - fully feathered and open-eyed. Kiwi parents do not need to feed their young because the chick can survive off the rich egg yolk for several days. At the end of this time, a kiwi chick may weigh only 80% of its hatching weight. After two or three days, enough of the yolk sac has been absorbed to allow the baby kiwi to stand and shuffle around the nest. This yolk sustains the chicks for their first 10 days of life – after that they are ready to forage for their own food.

Top to bottom:

1 day old Kiwi chick. Note the large yolk-filled abdomen. No wonder the Kiwi lays the largest eggs for its size of any bird!

5 day old Kiwi chick, Yolk almost all resorbed.

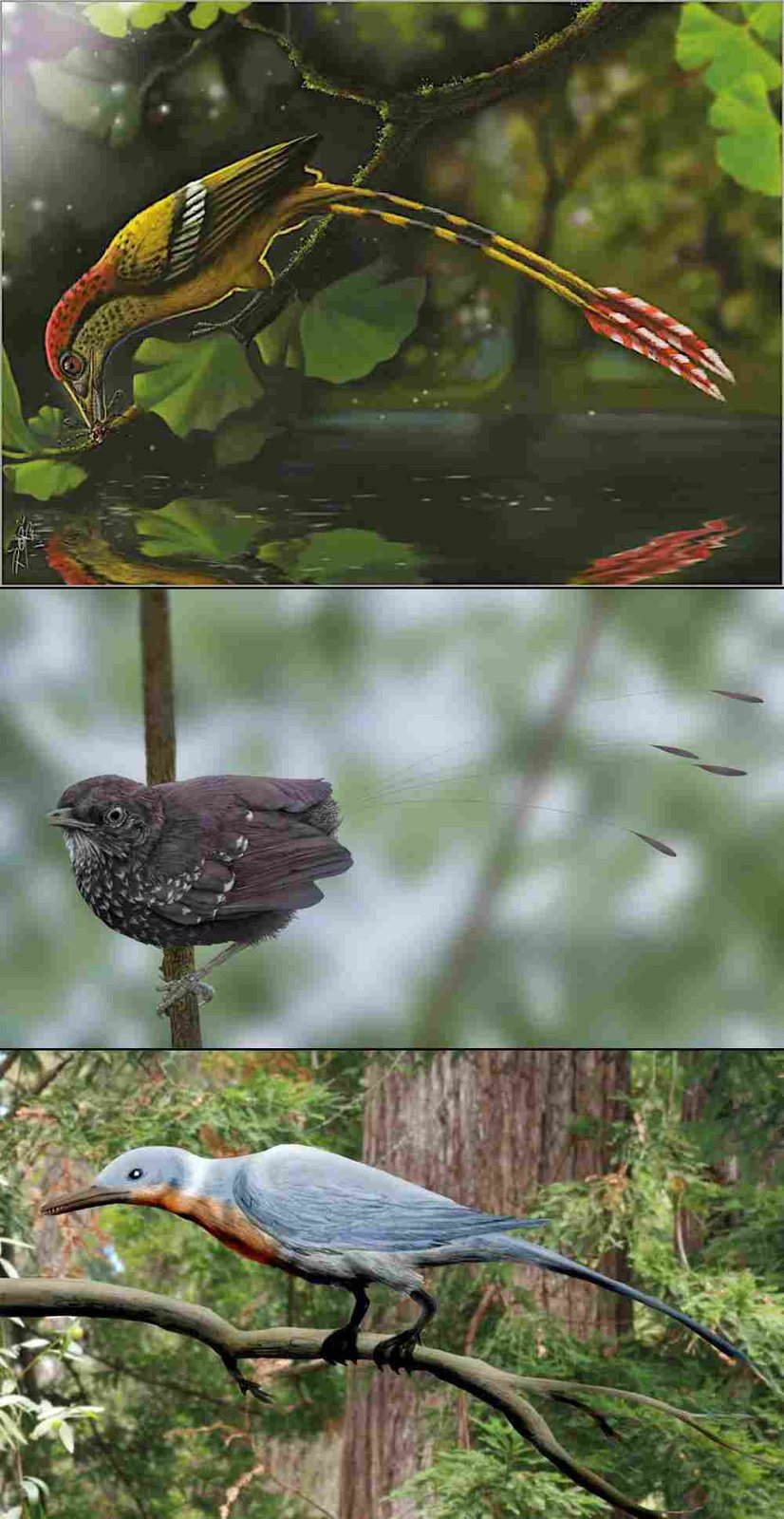

The extinct Enantiornithes are a group of extinct avialans ("birds" in the broad sense), the most abundant and diverse group known from the Mesozoic era. Almost all retained teeth and clawed fingers on each wing, but otherwise looked much like modern birds externally. The name "Enantiornithes" means "opposite birds", i.e. the opposite of modern birds. Known enantiornithine fossils include eggs, embryos, and hatchlings. An enantiornithine embryo, still curled in its egg, has been reported. These finds demonstrate that enantiornithine hatchlings had the skeletal ossification, well-developed wing feathers, and large brain which correlate with precocial or superprecocial patterns of development in birds of today. In other words, Enantiornithes probably hatched from the egg already well developed and ready to run, forage, and possibly even fly at just a few days old. So the extinct Enantiornithes (and pterosaurs) were also "superprecocial".

3 reconstrucuions of Enantiornithes:

Top to bottom:

a. Cratoavis.

b. Parvavis.

c. Shanweiniao cooperorum.

Lastly, not all large flightless birds are Ratites. Sylviornis is an extinct genus of stem-galliform bird containing a single species, Sylviornis neocaledoniae, or erroneously, "New Caledonian giant megapode" (Technically, this is incorrect because it has recently been found not to be a megapode). It was a huge flightless bird, 1.7 m (5.6 ft) long altogether, and weighing around 30 kg (66 lb) on average. It is the most massive galliform known to have ever existed. Even larger were the Dromornithidae, known as Mihirungs and informally as thunder birds or demon ducks. They were a clade of large, flightless Australian birds of the Oligocene through Pleistocene Epochs, long classified in Struthioniformes, but are now usually classified as galloanseres (with water fowls and game birds). One species, Dromornis stirtoni, was 3 m (9 ft 10 in) tall.

Restorations:

Top to bottom:

a. Sylviornis neocaledoniae.

b. Dromornis stirtoni.

[Information from Wikipedia and other sources]

Megapodes are an interesting Australasian family of birds closely related to the Gamebirds (Galliformes). They are also known as incubator birds or mound-builders, and are stocky, medium to large, chicken-like birds with small heads and large feet in the family Megapodiidae. Bird hatchlings, like new-born mammals, can be precocial where the young are relatively mature and mobile from the moment of birth or hatching. The opposite developmental strategy is called altricial, where the young are born or hatched helpless as in songbirds. Examples of precocial birds include the domestic chicken, many species of ducks and geese, waders and rails. Extremely precocial species are called "superprecocial". Megapodes are "superprecocial", hatching from their eggs in the most mature condition of any bird. They hatch with open eyes, bodily coordination and strength, full wing feathers, and downy body feathers, and are able to run, pursue prey, and in some species, fly on the same day they hatch. Megapodes do not incubate their eggs with their body heat as other birds do, but bury them. Their eggs are unusual in having a large yolk, making up 50 - 70% of the egg weight. The birds are best known for building massive nest mounds of decaying vegetation, which the male attends, adding or removing litter to regulate the internal heat while the eggs develop. However, some bury their eggs in other ways: there are burrow-nesters which use geothermal heat, and others which simply rely on the heat of the sun warming sand.

Nest Mounds and Nesting sites:

1. Top to bottom:

a. Malleefowl Nest Mound (Malleefowl nest mounds can be over 1m in height and 4m across. The male buries wet leaf litter in the mound, which gives off heat as it rots, acting as a natural incubator for the eggs. Throughout the breeding season, the male has to ensure that the temperature inside the mound is maintained at about 33°C. Temperature is maintained by digging the nest and by adding or removing sand).

b. Australian Brushturkey Nest Mound (They build large nests on the ground made of leaves, other compostable material, and earth, 1 to 1.5 metres high and up to 4 metres across. The eggs are hatched by the heat of the composting mound, the temperature of which is regulated by adding or removing material to maintain the temperature in the 33 to 35 °C incubation temperature range.The same nesting site is frequently used year after year).

c. Mound of the Orange-footed scrubfowl (Megapodius are best known for building a massive mound of decaying vegetation, which the male attends, adding or removing litter to regulate the internal heat while the eggs hatch)

2. Top to bottom:

a. Moluccan Scrubfowl burrows at nesting site (The nesting grounds are usually located in sun-exposed beach or volcanic soils.The Moluccan megapode is the only megapode known to lay its eggs nocturnally).

2. Close-up of Maleo nest.

3. Maleo Nesting Site (The Maleo is a mound builder that uses volcanic and solar-heated sand to incubate its eggs in large colonial nesting grounds).

3.Top to bottom:

a. Illustration of Malleefowl covering its Eggs with sand.

b. Pair of Malleefowls atop Nesting Mound.

Instead of a sharp dividing line between hatchlings that are precocial and those that are altricial, there is a gradient of precociality.

Precocial: There are four levels of precociality. Level 1 of development (precocial 1) is the pattern found in the chicks of megapodes (Australian Malee fowl, Brush Turkeys, etc.), which are totally independent of their parents ("superprecocial"). The megapode young are incubated in huge piles of decaying vegetation, and upon hatching dig their way out, already well feathered and able to fly. Precocial 2 development is found in ducklings and the chicks of shorebirds, which follow their parents but find their own food. The young of game birds, however, trail after their parents and are shown food; they are classified as precocial 3. Precocial 4 development is represented by the young of birds such as rails and grebes, which follow their parents and are not just shown food but are actually fed by them.

Semi-precocial: Hatched with eyes open, covered with down, and capable of leaving the nest soon after hatching (they can walk and often swim), but stay at the nest and are fed by parents. Basically precocial but nidicolus (young that remain in the nest), this developmental pattern is found in the young of gulls and terns.

Semi-altricial: Covered with down, incapable of departing from the nest, and fed by the parents. In species classified as semi-altricial 1, such as hawks and herons, chicks hatch with their eyes open. Owls, in the category semi-altricial 2, hatch with the eyes closed. If all young were divided into only two categories, altricial and precocial, these all would be considered altricial

Altricial: Hatched with eyes closed, with little or no down, incapable of departing from the nest, and fed by the parents. All passerines are altricial.

Megapodes are divided into 3 Groups:

1. Scrubfowl Group - 3 living genera

1a. Genus: Macrocephalon - 1 species, Maleo (Macrocephalon maleo).

Top to bottom:

a. Maleo (Macrocephalon maleo).

b. Hatchling. Note the fully formed flight feathers.

c. Comparative sizes of egg and newly hatched chick.

1b. Genus: Eulipoa - 1 species, Moluccan megapode (Eulipoa wallacei).

Top to bottom:

a. Moluccan scrubfowl (Eulipoa wallacei)

b. Moluccan scrubfowl in burrow laying eggs

1c. Genus: Megapodius - 13 species.

Here are 3 examples:

Top to botttom:

a. Micronesian scrubfowl (Megapodius laperouse).

b. Nicobar scrubfowl (Megapodius nicobariensis).

c. Philippine scrubfowl (Megapodius cumingii).

Another 2 examples:

Top to botttom:

a. Tongan scrubfowl (Megapodius pritchardii).

b. Orange-footed scrubfowl (Megapodius reinwardt).

c. Orange-footed scrubfowl, juvenile with adult wing feathers.

2. Malleefowl Group - 1 genus

2a. Genus: Leipoa - 1 species, Malleefowl (Leipoa ocellata)

Top to bottom:

a. Malleefowl (Leipoa ocellata).

b. Hatchling. Again, note the fully developed wing feathers.

c. Hatchling in hand.

3. Brushturkey Group - 3 living genera

3a. Genus: Alectura - 1 species, Australian brushturkey (Alectura lathami)

Top to botttom:

a. Australian brushturkey (Alectura lathami).

b. Hatchling. Note the fully developed wing feathers.

c. Hatchling, showing wing feathers.

3b. Genus: Aepypodius - 2 species

Top to botttom:

a. Waigeo brushturkey ( Aepypodius bruijnii).

b. Wattled brushturkey (Aepypodius arfakianus).

c. Wattled brushturkey Hatchling.

3c. Genus: Talegalla - 3 species

Top to bottom:

a. Black-billed brushturkey (Talegalla fuscirostris).

b. Red-billed brushturkey (Talegalla cuvieri).

c. Collared brushturkey (Talegalla jobiensis).

4. Extinct Giant Malleefowl

Top to bottom:

a. Progura gallinacea, the extinct Giant Mallee fowl.

b. Comparisons of skeletal elements of Progura gallinacea and Leipoa ocellata to indicate relative size .

Megapodes are the only extant birds with "superprecocial" chicks, which leave the nest immediately after hatching and do not receive any post-hatching parental care. Kiwi hatchlings likewise spend only a very short time in the nest and though not really "superprecocial" (they are advaced level 2 precocial), are more precocial than the young of most other extant birds. Kiwi chicks hatch as mini-adults - fully feathered and open-eyed. Kiwi parents do not need to feed their young because the chick can survive off the rich egg yolk for several days. At the end of this time, a kiwi chick may weigh only 80% of its hatching weight. After two or three days, enough of the yolk sac has been absorbed to allow the baby kiwi to stand and shuffle around the nest. This yolk sustains the chicks for their first 10 days of life – after that they are ready to forage for their own food.

Top to bottom:

1 day old Kiwi chick. Note the large yolk-filled abdomen. No wonder the Kiwi lays the largest eggs for its size of any bird!

5 day old Kiwi chick, Yolk almost all resorbed.

The extinct Enantiornithes are a group of extinct avialans ("birds" in the broad sense), the most abundant and diverse group known from the Mesozoic era. Almost all retained teeth and clawed fingers on each wing, but otherwise looked much like modern birds externally. The name "Enantiornithes" means "opposite birds", i.e. the opposite of modern birds. Known enantiornithine fossils include eggs, embryos, and hatchlings. An enantiornithine embryo, still curled in its egg, has been reported. These finds demonstrate that enantiornithine hatchlings had the skeletal ossification, well-developed wing feathers, and large brain which correlate with precocial or superprecocial patterns of development in birds of today. In other words, Enantiornithes probably hatched from the egg already well developed and ready to run, forage, and possibly even fly at just a few days old. So the extinct Enantiornithes (and pterosaurs) were also "superprecocial".

3 reconstrucuions of Enantiornithes:

Top to bottom:

a. Cratoavis.

b. Parvavis.

c. Shanweiniao cooperorum.

Lastly, not all large flightless birds are Ratites. Sylviornis is an extinct genus of stem-galliform bird containing a single species, Sylviornis neocaledoniae, or erroneously, "New Caledonian giant megapode" (Technically, this is incorrect because it has recently been found not to be a megapode). It was a huge flightless bird, 1.7 m (5.6 ft) long altogether, and weighing around 30 kg (66 lb) on average. It is the most massive galliform known to have ever existed. Even larger were the Dromornithidae, known as Mihirungs and informally as thunder birds or demon ducks. They were a clade of large, flightless Australian birds of the Oligocene through Pleistocene Epochs, long classified in Struthioniformes, but are now usually classified as galloanseres (with water fowls and game birds). One species, Dromornis stirtoni, was 3 m (9 ft 10 in) tall.

Restorations:

Top to bottom:

a. Sylviornis neocaledoniae.

b. Dromornis stirtoni.

[Information from Wikipedia and other sources]

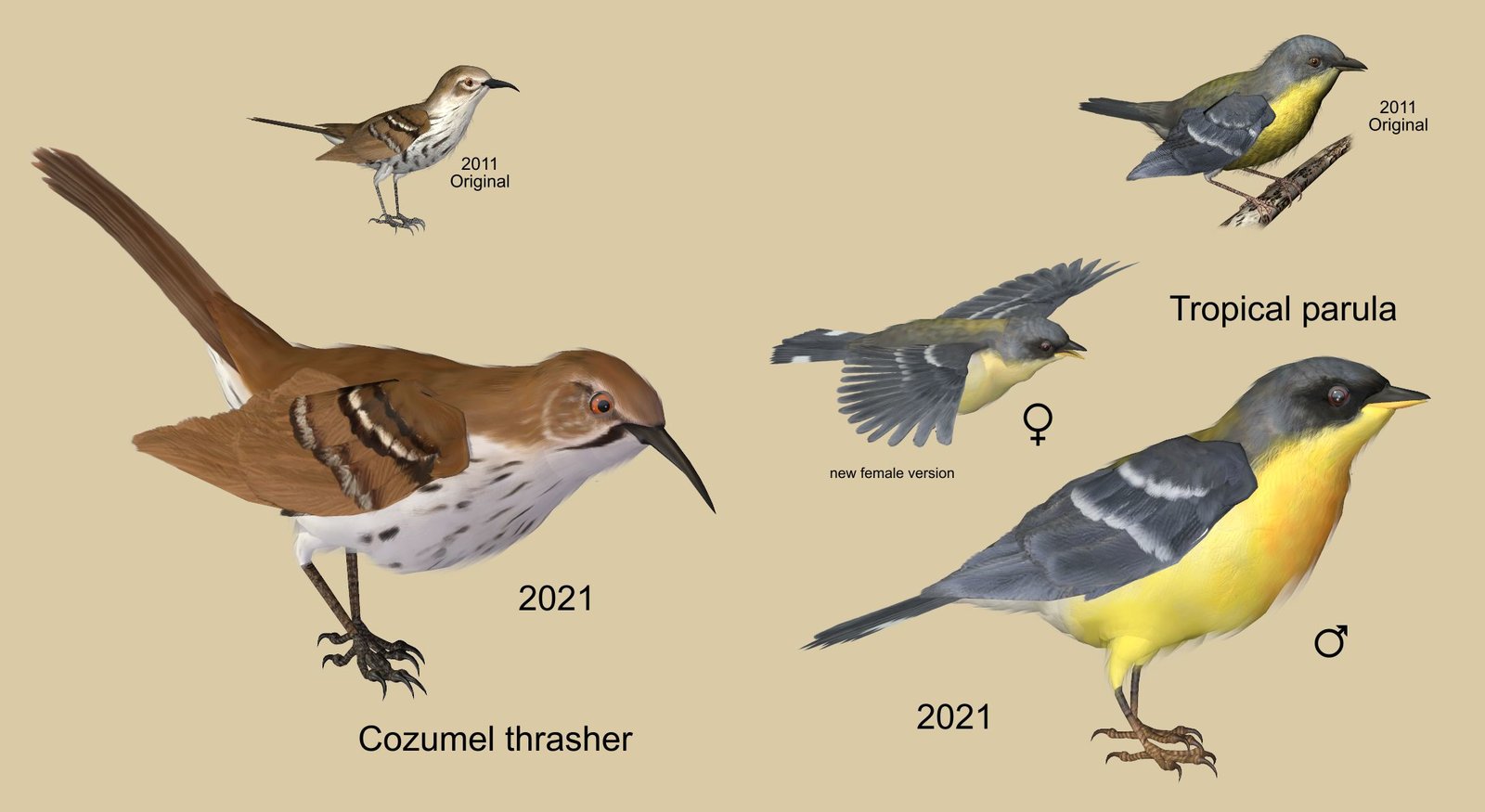

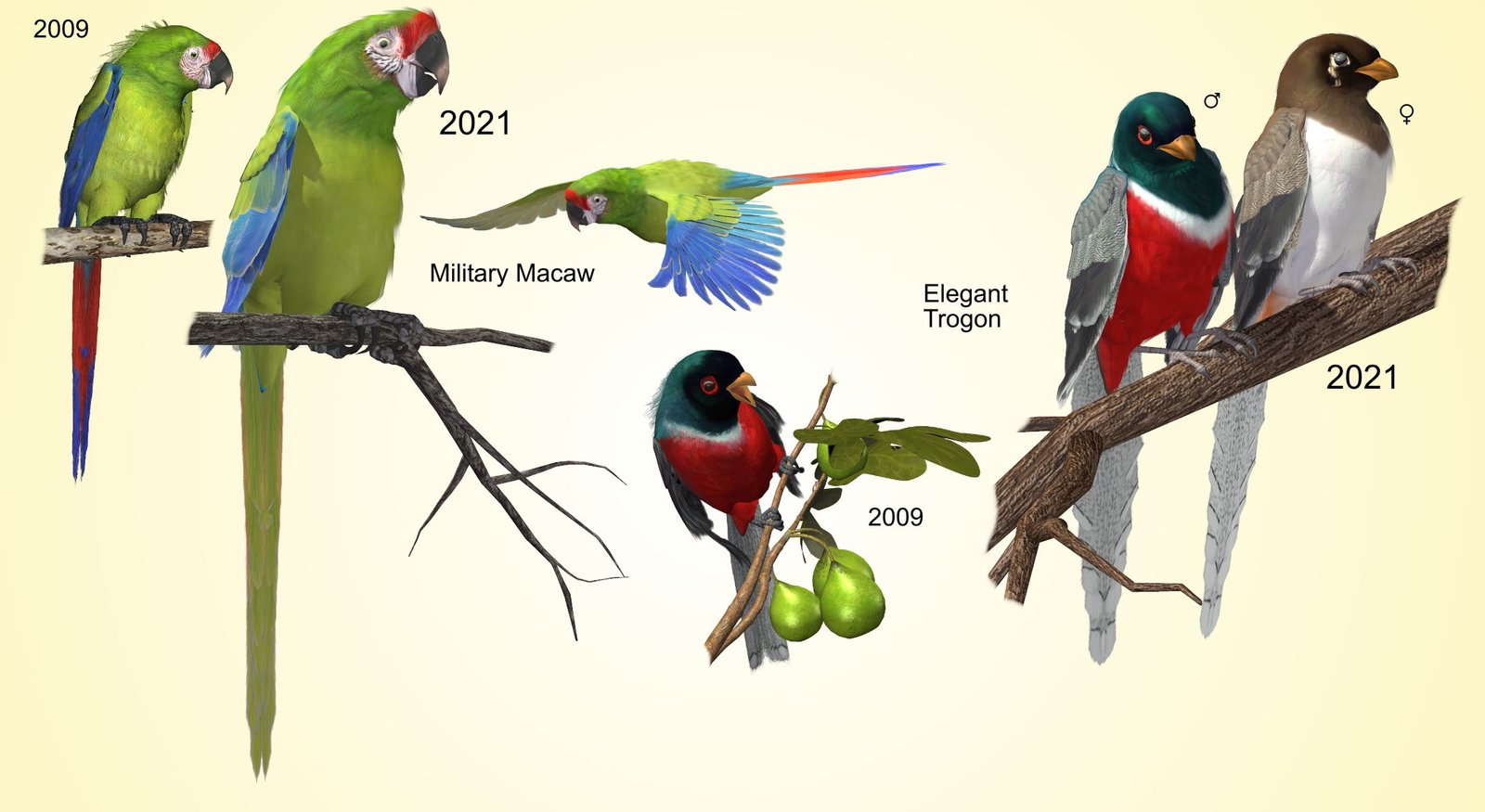

Here's a peek at some of the Yucatan Birds... before and after

Steadily working through Yucatan (which has some of my favorite birds and, of course, reminds me of an incredible trip I took to the interior of Belize. It was sort like Bird Boot Camp. We spent 5 days with an ornithologist by our side and started birding at dawn by watching parrots by over the Mayan Jaguar Temple and finished in the dark, "Owling" on a deserted airstrip. Three-quarters of the birds in the Yucatan set, I saw there in those 5 days.

There's some significant changes on some these... part of the "updated" sets I've been showing (obviously) isn't just the addition of physical renderer support. In most cases, the revised model sets offer dramatically better shaping of the birds, bringing them closer to their actual counterparts. Also, most textures have been reworked to offer more realistic birds with proper markings. A good example of this is the Red-legged Honeycreeper which there weren't very many online references, or even descriptions of, back in 2009 when the bird was created. I only had a physical field guide book that showed an illustration of the male perched. There's no way I would have ever guessed that blue and black colored male's wing undersides were yellow.

I'll eventually return to my Guineafowl model for another Gamebird sets and some of these will probably be included. I have 3-4 gamebird sets that I've already mapped for once I get all the updates done....Megapodes are an interesting Australasian family of birds closely related to the Gamebirds (Galliformes)....

I've reworked and finished one of the stars of my updated Yucatan set, the Royal Flycatcher. Looking at the crests, it's easy to see where the inspiration for Mayan and Aztec headdresses came from.

I've actually seen one of these birds when I was in Belize... they're amazing... but to be truthful, it's exceptionally rare when they do display their crests (only during mating or in extreme peril). Of course, that doesn't stop us 3-D artists from getting them to show them in renders.

The Poser side of Yucatan is done and I'll converting and fitting the birds for DAZ Studio tomorrow. The set, I'm hoping have it re-released by the end of this month. Since a whopping 15 additional birds have been added to its original 19 (mostly dimorphic females and few subspecies), the price will be going up $5 to $24.95 (of course, it's still a free update to those who already own it).

Birds included (new in bold type):

Kingfishers (Order Coraciiformes)

* American Pygmy Kingfisher (m/f)

* Lesson's Motmot (originally called Blue-crowned Motmot)

Parrots and Cockatoos (Order Psittaciformes)

* Military Macaw

Perching Birds

Cardinals, Tanagers & their Allies:

* Red-legged Honeyeater (m/f nominate and m/f Race carneipes)

Crows, Jays and their Allies

* Blue-throated Magpie-jay (m/f/juvenile in northern variant and m/f in southern variant)

* Yucatan Jay (adult/immature/juvenile)

New World Warblers & their Allies

* Tropical Parula (m/f)

Orioles, Blackbirds & their Allies

* Orange Oriole (m/f)

Swallows & their Allies

* Mangrove Swallow

Thrushes, Oxpeckers & their Allies

* Cozumel Thrasher

Tyrant Flycatchers & their Allies

* Royal Flycatcher (m/f nominate and m/f Race mexicanus)

* White-collared Manakin (m/f)

Trogons and Quetzals (Order Trogoniformes)

* Elegant Trogon (m/f)

* Resplendent Quetzal (m/f)

Woodpeckers and Toucans (Order Piciformes)

* Chestnut-headed Woodpecker (m/f)

Birds included (new in bold type):

Kingfishers (Order Coraciiformes)

* American Pygmy Kingfisher (m/f)

* Lesson's Motmot (originally called Blue-crowned Motmot)

Parrots and Cockatoos (Order Psittaciformes)

* Military Macaw

Perching Birds

Cardinals, Tanagers & their Allies:

* Red-legged Honeyeater (m/f nominate and m/f Race carneipes)

Crows, Jays and their Allies

* Blue-throated Magpie-jay (m/f/juvenile in northern variant and m/f in southern variant)

* Yucatan Jay (adult/immature/juvenile)

New World Warblers & their Allies

* Tropical Parula (m/f)

Orioles, Blackbirds & their Allies

* Orange Oriole (m/f)

Swallows & their Allies

* Mangrove Swallow

Thrushes, Oxpeckers & their Allies

* Cozumel Thrasher

Tyrant Flycatchers & their Allies

* Royal Flycatcher (m/f nominate and m/f Race mexicanus)

* White-collared Manakin (m/f)

Trogons and Quetzals (Order Trogoniformes)

* Elegant Trogon (m/f)

* Resplendent Quetzal (m/f)

Woodpeckers and Toucans (Order Piciformes)

* Chestnut-headed Woodpecker (m/f)

Will be looking forward to it. Given the amount of work going into these updates, I'm willing to re-purchase most of the ones that get released one at a time or at intervals of a month or so.

Wouldn't care to have to repurchase everything at once, by any means. I'll also probably wait for the transfer information to be done before going to collect the environments and architectural sets.

I am using birds in my renders much more often with the new versions. Even if it's still mostly throwing the flock formations into most of my exterior images.

Wouldn't care to have to repurchase everything at once, by any means. I'll also probably wait for the transfer information to be done before going to collect the environments and architectural sets.

I am using birds in my renders much more often with the new versions. Even if it's still mostly throwing the flock formations into most of my exterior images.

Here's the updated version of my Royal Flycatcher in Iray from SBRM Yucatan (hopefully re-released around the end of the month).

Flint_Hawk

Dances with Bees

They sure are!

I'm back to finishing up the update on Cool and Unusual v2... one interesting thing I discovered on this species is that despite their bulky appearance, they are very agile fliers and part of the Tyrant Flycatcher family... their name "Cock-of-the-Rock" comes from their common appearance on the rocky slopes of the Andes

I'm struggling through the last two reworkings of Cool and Unusual Birds v2, the male Lesser and Greater Birds of Paradise. Much like the Lyrebird, they have a complex tail that's providing all sorts of challenges for me to work out.

With the lyrebirds, I chose to go to a multipart rigging system that resulted in 184-part tail. That allows complete control of every tail feather but can be a nightmare to pose individually (that why I included a number of baseline poses).

In this instance, I decided to go with a approach that more resemble where I went with the peafowl, grouping segments of the tail into seven pieces (left and right) on the plume feathers and 13 pieces (left and right) on the two center "point" feathers. There's still challenges ahead, but it's getting there.

Below are images of WIP on the male Lesser Bird of Paradise. I expect Yucatan's update to be released within a week or so and this update to be ready mid-to-late September, followed by Amazon and the two Hummingbird sets, late Fall.

With the lyrebirds, I chose to go to a multipart rigging system that resulted in 184-part tail. That allows complete control of every tail feather but can be a nightmare to pose individually (that why I included a number of baseline poses).

In this instance, I decided to go with a approach that more resemble where I went with the peafowl, grouping segments of the tail into seven pieces (left and right) on the plume feathers and 13 pieces (left and right) on the two center "point" feathers. There's still challenges ahead, but it's getting there.

Below are images of WIP on the male Lesser Bird of Paradise. I expect Yucatan's update to be released within a week or so and this update to be ready mid-to-late September, followed by Amazon and the two Hummingbird sets, late Fall.

Last edited:

Flint_Hawk

Dances with Bees

Ken's Songbird ReMix Yucatan are now in the store at Renderosity:

Songbird ReMix Yucatan 3D Models HiveWire3D Ken _Gilliland (renderosity.com)

Songbird ReMix Yucatan 3D Models HiveWire3D Ken _Gilliland (renderosity.com)

Yes,it is... though I wasn't expecting it to appear so soon  I had to rush to get the new manual and art up on my website this afternoon.

I had to rush to get the new manual and art up on my website this afternoon.

I'm hoping to have Cool and Unusual v2 ready mid-next month and Amazon at the end of the next month. From there, I'll probably tackle the two hummingbird volumes and do a couple new sets, though I can't decide which ones yet (Bee-eaters, Kingfishers, Hummingbirds v3, Bees of the World v2, Seabirds v3, Prairie Chickens & Sage Grouses and the list goes on...)

I'm hoping to have Cool and Unusual v2 ready mid-next month and Amazon at the end of the next month. From there, I'll probably tackle the two hummingbird volumes and do a couple new sets, though I can't decide which ones yet (Bee-eaters, Kingfishers, Hummingbirds v3, Bees of the World v2, Seabirds v3, Prairie Chickens & Sage Grouses and the list goes on...)